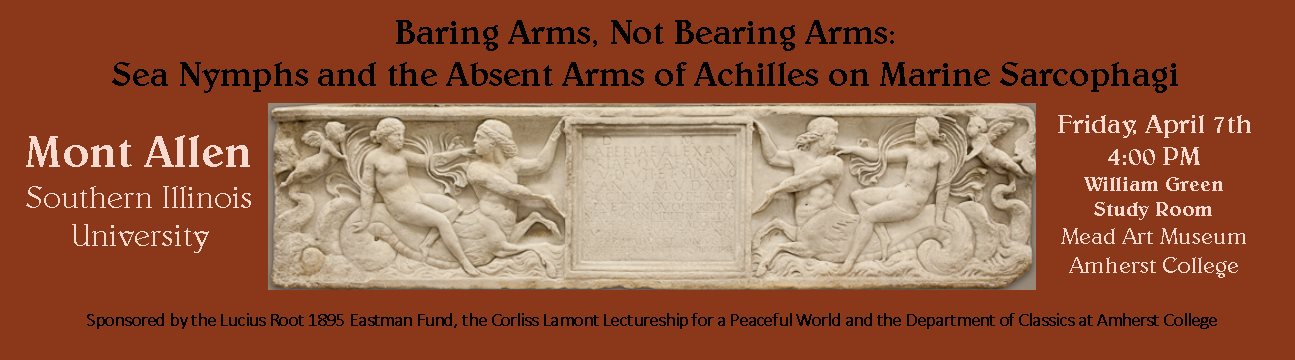

On Friday, April 7, the author of this blog will give a lecture at Amherst College on a gorgeous — and gorgeously idiosyncratic — marine sarcophagus recently acquired by Amherst's Mead Art Museum. All are welcome.

As reported by The Daily Mail, The BBC, The Telegraph, and The New York Times, among others, a Roman sarcophagus (or at least, the front slab of one) has been discovered on the grounds of Blenheim Palace, where it has spent the last century in service as a tulip planter. This lenoid piece (a coffin shaped like a lenos: a wine vat) features the lions-head bosses typical for this shape, while the figural frieze itself — a Dionysiac scene of the inebriated god approaching the sleeping form of his beloved Ariadne, her own pose echoed by that of Hercules reclining boozily at left (an unusual addition) — plays on the lenos's associations with wine. The dates reported for the piece are a mess. Most of the sources above describe it as "dating back to A.D. 300" or "300 AD" — but then go on to quote spokesmen who place the carving in the 2nd century (i.e., well over a century earlier), with no notice of the resulting chronological inconsistency. In truth, neither set of reported dates can be correct. AD 300 is far too late for this work. But the 2nd century is just as clearly too early, as an eye to the carving technique reveals. (Just look at the drill-heavy treatment of the lions' manes.) A 3rd-century date, tilting earlier rather than later — the 220s AD, or perhaps even the 230s — seems most likely. A wee plug here. The upcoming 2017 Annual Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America — convening this January 5-8 in Toronto — features an organized session devoted entirely to Roman sarcophagi. With six papers and two respondents (among them Ortwin Dally, Director of the DAI-Rome), it offers a full lineup of sarcophagine (sarcophagal? sarcophagoidal?) delight.

Session 6I: New Research on Roman Sarcophagi: Eastern, Western, Christian Saturday, Jan. 7, 1:45 - 4:45 pm Chairs: Sarah Madole (CUNY—BMCC) and Mont Allen (Southern Illinois University) (1) "Sarcophagus Studies: The State of the Field (as I see it)" Bjoern C. Ewald (Universit of Toronto) (2) "Roman Sarcophagi from Dokimeion in Asia Minor: Conceptual Differences between Rome and Athens" Esen Öğüş (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich) (3) "A New Mythological Sarcophagus at Aphrodisias" Heather N. Turnbow (The Catholic University of America) (4) "Beyond Grief: A Mother's Tears and Representations of Semele and Niobe on Roman Sarcophagi" Sarah Madole (CUNY—BMCC) (5) "Strutting Your Stuff: Finger Struts on Roman Sarcophagi" Mont Allen (Southern Illinois University) (6) "Love and Death: Jonah as Endymion in Early Christian Art" Robert Couzin (independent scholar) (7) Response Christopher H. Hallett (U.C. Berkeley) (8) Response Ortwin Dally (Deutsches Archäologisches Institut) National Museum of Beirut reopens basement featuring 31 anthropoid sarcophagi, Icarus sarcophagus12/6/2016 This is one of the most heart-warming developments that I've ever had the pleasure of blogging.

Abu Dhabi's The National reports that the National Museum of Beirut has — after 41 years of closure following the outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War in 1975 — reopened its basement galleries. Finding itself directly on the infamous Green Line that bisected Beirut during the Civil War, the museum and its objects were immediately imperiled by civil strife and looting. Read the full report in The National of the extreme measures to which then director of antiquities Maurice Chehab went in order to safeguard the collection in the basement. The story is astonishing. The highlight of the collection is the world's largest series of anthropoid sarcophagi: 31 in all, all from Phoenician Sidon and carved between the 6th and 4th centuries BC. Also figuring prominently in the reopened galleries is a fragment of a Roman sarcophagus from Beirut itself depicting Icarus standing beside the wing-crafting Daedalus, according to the Daily Mail. The scene is fantastically rare: I know of no other Roman sarcophagus that shows it.

As detailed by Artlyst, London's Ordovas gallery is exhibiting a collection of works on marine themes. Titled The Big Blue, it features a fragment of an Antonine marine sarcophagus showing a Nereid and Tritons (visible at the far right in the photos below), beside works by Francis Bacon, Gustave Courbet, Max Ernst, Pablo Picasso, Piet Mondrian, Yves Klein, Damien Hirst, and others. Although one wonders about the provenance of the piece, it is lovely to see a Roman sarcophagus celebrated for its relevance amidst such famous modern company. The show remains on display until December 12. As reported by the Tribune de Genève — and later covered in greater detail by the Tages-Anzeiger (many thanks to Christian Russenberger for the link) — a Swiss public prosecutor has ordered that a Roman sarcophagus deposited in the Geneva Freeport warehouse in 2010 and subsequently seized by Swiss Customs during an inventory check later that year be returned to Turkey. The piece itself is exquisite: a creamy Docimean specimen, likely Antonine in date, showing the Twelve Labors of Hercules. As detailed in earlier blog posts (here, here, and here), Metropolitan sarcophagi (i.e., those from the city of Rome itself) devoted to the Labors of Hercules typically array the hero's first ten labors on the front of the chest in narrative order, with the eleventh and twelfth depicted on the short ends, and nothing on the back (as usual for Metropolitan works), This piece, in contrast, strews the vignettes around all four sides — as expected for an eastern product — in no discernable order.

Following several years of renovation, the Saint Louis Art Museum's collection of ancient art has recently reopened with a fresh face, thanks to reinstallation by Assistant Curator Lisa Çakmak.

The Roman gallery now prominently features a fragment of a sarcophagus showing the Twelve Labors of Hercules (inv. 138:1987). The proportions of this Antonine fragment — its 1.42 meters must represent less than half of the original length — are absolutely massive. This was a monumental piece indeed. Its composition also departs from the standard in unexpected ways. Most noticeably, our hero here turns his torso to the left rather than right when bludgeoning the Hydra (contrast with the pieces in Mantua and Rome's Palazzo Altemps) — a choice that quirkily interrupts the narrative's rightward flow.

- Jaś Elsner, "Introduction".

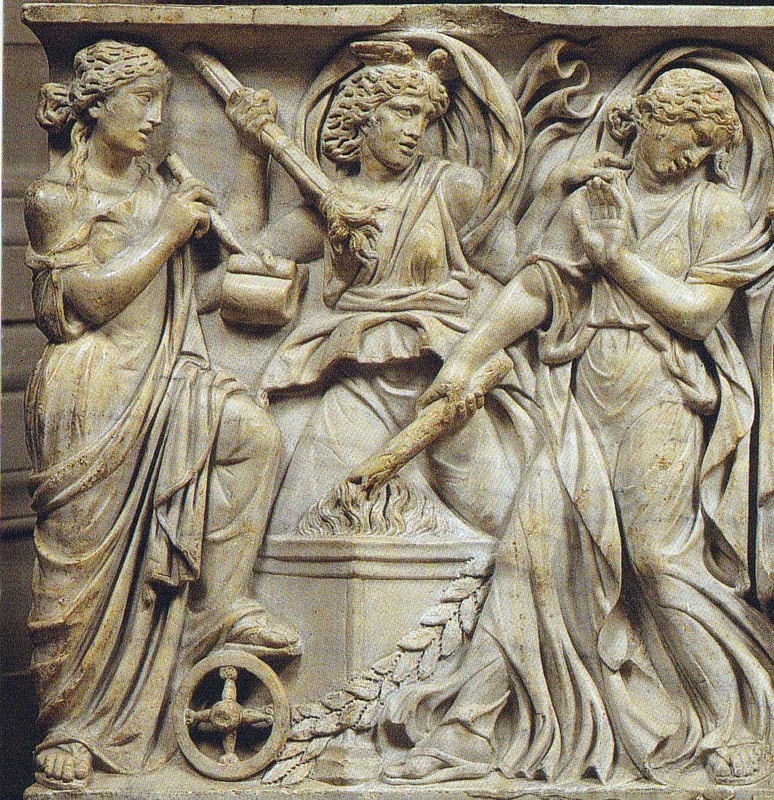

This sarcophagus is centered on the figure of Dionysus, god of wine, shown too intoxicated to stand. A helpful Satyr, a member of the god's debauched retinue, has to prop the tipsy deity up. Flanking Dionysus on both sides are personifications of the four seasons, symbols of plenty and abundance. I feature this piece, however, not for its endearing subject matter, but for its sculptural technique. It illustrates Roman carvers' ever greater reliance on the drill. Although the drill had been employed for working marble as far back as the Archaic period in Greece and was already widely used by the Early Classical period, nothing compared to the popularity it enjoyed in Roman hands, where it was used to render a wide variety of surface effects. This depended on a fundamental change in attitude towards traces of tooling: a willingness among Romans to advertise, rather than hide, tool marks. This stood in marked contrast to earlier practice. Greek sculptors had already employed the drill extensively for carving; but the Archaic and Classical ideal was a final surface devoid of any trace of tooling. Hence sculptors of these periods took obsessive care to efface all such marks, whether of chisel or drill. Hellenistic carvers show greater tolerance for tool marks, and extend this even to the drill, whose traces they often leave. But it is Roman sculptors who purposefully showcase the tool, actively foregrounding its distinctive optical bite. This flashy use of the drill for visual effects on sarcophagi seems to begin a little after the middle of the second century, in the mid-Antonine period. Used very sparingly at first, it was gradually put to ever greater use. By the latter part of the third century its grooves, channels, and isolated bore holes had taken over the carved surface, becoming the main means of rendering optical effects. This was especially the case in the face and hair of figures. As illustration of this artistic mode, consider the sarcophagus here, a piece likely carved during the reign of Constantine. Cast your eyes on the tiny cupid perched on the shoulder of the third season from the left. The detail shot makes things clear: his wee face has been given ‘features’ not through any plastic modeling with the chisel, but by simply drilling six holes into his amorphous blob of a head to index the eyes, nostrils, and the corners of the mouth. You can't help but think that this shouldn't work, because the style produces an utterly unrealistic surface. The real human form is not, after all, pockmarked and beehived with numerous cavernous holes. Yet this seldom strikes the viewer. This is because the drillwork serves as highly effective visual accenting: since the holes are used to emphasize areas where the eye is normally arrested anyway (the genitals, for example, or the eye itself), or features that the eye is normally accustomed to differentiating (such as the point near the knuckles where the fingers separate), its optical effects are often perceived as ‘naturalistic’ — especially at a distance — even though the impossible surface form that it produces is profoundly artificial. Comments warmly invited. (The Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work equally well.) A previous post featured the mysterious case of the phantom ponytail — a Roman sarcophagus whose occupant, portrayed on the front, appeared to be sprouting phantasmic locks of hair from above his ear. I return to this marvelous piece because a recent trip to Rome has provided me with better photographs (above). These show the marks of recutting, and the ghostly traces of the prior owner's ponytail, in better light. Several readers asked me about the hairstyle of Isis's son Harpocrates, the mythic child whose coiffure was adopted by male devotees of Isis (including this coffin's original owner). Below is a photograph of a bronze statue of the wee god, now in San Francisco's Legion of Honor. Dated to the early 3rd century, it's roughly contemporaneous with our sarcophagus. You can't miss the prominent sidelock. Comments warmly invited. (Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.)

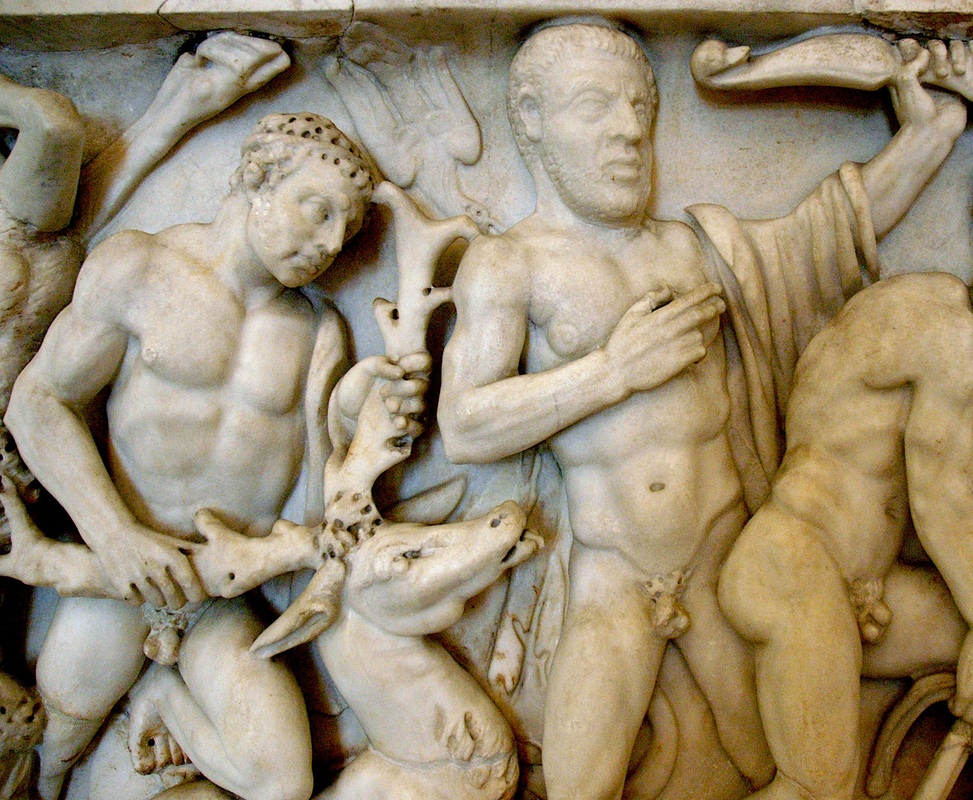

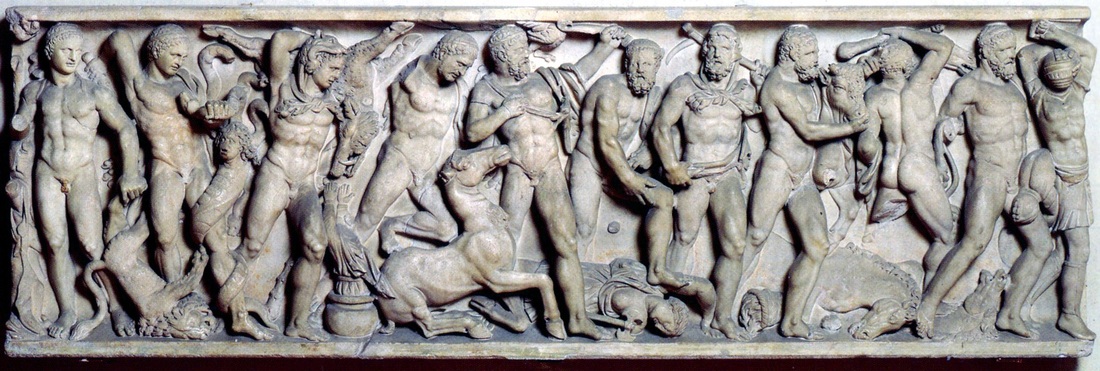

This elaborate Roman sarcophagus is entirely devoted to the Labors of Hercules. Its strategy is to array the twelve episodes in a sequence which stretches across the entire front face of the coffin and wraps around onto the (now missing) ends.

If you’re thinking that this looks oddly familiar, you’re right to wonder. Our previous post looked at another sarcophagus which similarly featured the Labors of Hercules. Here it is again:

You’ll notice immediately how similar the compositions are. Sure, there are minor differences: the head and torso of the Hydra on today’s piece (second episode from the left) is considerably less monstrous. Eurystheus looks even more ludicrous as he takes refuge in a sunken pithos (a large partially-submerged storage jar) from the Erymanthian Boar slung over Hercules’ shoulder. This sarcophagus gives us two Stymphalian Birds, not one, and neither appears to nibble on Hercules’ bow (instead, one appears to be dive-bombing our hero’s shoulder). And Hippolyta, the Amazon Queen, looks not dead but worrisomely elastic and gumby-like as she spins her head around to look up at her conqueror as he strips her of her girdle. But taken as a whole, these compositions are almost identical.

Was the carver of the second sarcophagus (today’s piece) simply copying the composition of the first directly? It seems unlikely. Some 70 to 80 years separate these two pieces. And the first would almost surely have been in a private family tomb — i.e., not displayed in some public place where other artists might have seen (and copied) it. It turns out that these two more-or-less identical pieces are hardly unique in their copy-cat-dom. Numerous sarcophagi feature the adventures of Orestes, for example, laid out in exactly (or almost exactly) the same way every time. The same holds for sarcophagi staging the murderous story of Medea, the Hunt of the Calydonian Boar, and numerous other myths. They are our best evidence for what was clearly a widespread practice among Roman sculptors: the reliance on so-called pattern books, or copy books: picture books featuring drawings of popular compositions, which carvers could refer to for inspiration as they translated them into stone. Why bother developing one’s own novel composition — and risk months of wasted labor and material if it failed — when one could simply adopt a well-known composition guaranteed to work? Something else you’ve doubtless noticed: the head of the middle Hercules on today's piece — the one shooting the Stymphalian Birds — looks substantially different from the others. That’s because it’s a portrait: a portrait of the deceased man interred within the sarcophagus itself. It may strike us as odd, to see the portrait head of a rather grumpy looking middle-aged Roman man plopped atop the idealized body of Hercules. But it was common Roman practice on sarcophagi between roughly 220 and 250 AD. The Greek mythological imagery on sarcophagi was intended, as a rule, to be applied to the dead Romans buried inside them. Equipping these mythological characters with portrait features of the deceased was a way to make the metaphorical connection between them emphatic: it demanded that the viewer read the mortal through the mythic, and the mythic through the mortal. Which brings us back to the epic saga of facial hair. Hercules on these sarcophagi begins his labors clean-shaven, and develops a beard along the way. We noted last time that it was a strategy for rendering, within the static and immobile terms of stone, the passage of time: a reminder that Hercules’ labors stretched over years. But now, goaded by the portrait to read this dead Roman in terms of the Greek hero, we realize that this device serves an additional purpose. It invites the viewer to imagine the entire adult life of the deceased man — from beardless youth to bearded age — as a single lifelong string of glorious labors and deeds, just like Hercules’. Bombastic? Absolutely. But effective.

Comments warmly invited.

(Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.) This gorgeously carved mythological sarcophagus presents a composition so crowded that you might think it undecipherable. But once you know a few tricks of Roman visual logic, the unruly mass of bodies settles down into order. This sarcophagus stages the Twelve Labors of Hercules. Its method is to line the episodes up in a single row, with no borders separating them, and to repeat the figure of the hero himself twelve times, once for every labor. At this point you may be thinking “Twelve labors?! I only see ten.” Right you are: what we have here is simply the front slab of the sarcophagus. The two missing labors would have appeared on the coffin’s short ends (now missing). So which labors do we have on the front? From left to right, Hercules....

Many of the visual details are whimsical, even quirky. But it’s the changing state of Hercules’ facial hair that is the most interesting. Our hero stays clean-shaven for his first four labors. But then, beginning with the Stymphalian Birds, he suddenly sprouts a beard, and sports it during his remaining exploits. What to make of this? It’s tempting to joke that his labors simply left him too busy to shave. But that doesn’t quite capture the purpose of this artistic device. The progression from baby-faced to bearded hero serves, above all, as a concise way to indicate time’s long passage. The labors took twelve years to complete, occupying the better part of Hercules’ adult life. The development of his facial hair thus indicates the direction of the narrative and tracks the progression of time, rendering it visible within the static and immobile terms of carved stone. We look at another Hercules sarcophagus in our next post: Why does Hercules look like Uncle Rufus?

Comments warmly invited.

(Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.) An earlier post ("Shouldering Responsibility for Recutting") was devoted to a child's sarcophagus with several unusual features. One of them had to do with the child's clothing: she (turned into a portrait of a he) was portrayed wearing sensual off-the-shoulder drapery. Such suggestive garb would be unexpected even for a grown woman: unless she was adopting the guise of Venus, no respectable Roman woman would show herself (un)clad in this way. It would seem an even odder choice for a child. Yet the small dimensions of the coffin left no doubt that it was intended for a child, or at least a juvenile. I filed it away mentally as yet another unique specimen, one of the hundreds of quirky pieces that make the study of Roman sarcophagi endlessly alluring. But it turns out that, while quirky, this feature isn't unique. A colleague has brought another specimen to my attention — from, in fact, the same museum. (The Vatican's collections stretch for halls and halls....) This one, shown above, features a festive procession (in ancient Greek, a thiasos) of various marine creatures: sea nymphs, sea centaurs, dolphins, and, at the far ends, pendant vignettes showing Europa's watery abduction at the hands (horns?) of Zeus in bull's form. The two sea centaurs in the center bear a clipeus medallion framing a portrait of the deceased. As so often, the portrait itself is unfinished: the facial features are still blank, waiting for the final customization once a customer had been found. But the rest of the bust has already been executed — and it clearly shows the same revealing off-the-shoulder drapery as our other piece. Finally, this coffin too was intended for a juvenile: its dimensions are too small for an adult. What's the deal with the sexy kids? I don't have an answer yet — only the beginnings of a pattern. I can't help but wonder, though, whether these pieces were intended for girls who died close to the age of marriage (as young as 12 years for aristocratic girls), their revealing garb meant to underscore the poignancy of a life cut down before its beauty could find adult consummation.

Comments warmly invited.

(Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.) Why does this young man appear to be sprouting phantasmic locks of hair from above his left ear? It seems that he's shadowed by the ghostly ponytail of the coffin's previous owner. The portrait has clearly been recut, and the original must have showed a boy devoted to the goddess Isis: her young male followers proclaimed their devotion by shaving their heads, razoring off everything except a single long tuft of hair above the ear. (The hairstyle was modelled on that of the mythic child Harpocrates, son of Isis.) Sheer need must have driven the later family to choose this piece — with its prior owner's prominently protruding hairstyle — for reappropration and recutting. Why not choose one with a portrait of a non-devotee, whose hair would be much less troublesome to erase? Or else simply make better use of abrasives to take down the background plane around the head, fully scrubbing off any lingering halo? Clearly money — or time — was limited, and the family made do with the used piece they had at hand: a striking reminder of the exigencies of death, the high rates of infant mortality in the ancient world, and above all, the frequent recarving and reuse of sarcophagi in antiquity by Romans themselves. ADDENDUM I return to this piece in a later post: The Phantom Ponytail returns. Comments warmly invited. (Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.) Who is that boy who stands languidly with arms atop his head, doing his best impression of a male pin-up on both ends of this sarcophagus? And why is there a cupid at his feet, pointing to what looks like a theater mask on the ground? If he weren't doubled up, you might think he was Dionysus, or even Apollo, given the youthful features and the erotic posturing. But since he's duplicated, he probably doesn't represent a deity: Roman carvers often duplicated generic figures, and sometimes even mythological mortals; but they usually refrained from doubling up a god. So who is he? The answer: Narcissus. He's very uncommon: out of roughly 15,000 surviving Roman sarcophagi, only 5 (!) show Narcissus. But this is he. The cupid — that wee godling of desire — who stands at his feet is pointing not to a theater mask, but to Narcissus's own reflection. Which Narcissus, of course, is admiring: the erotic nature of his pose reflects his response to his own image. The composition seems bizarre to us: doesn't the Narcissus of Ovid's story (Metamorphoses 3:402-436) bend over the pool, or rather, lie beside it, rather than stand erect over it? Indeed he does. But the formal parameters of this particular format of sarcophagus, which left a tall but narrow field for mythological depiction at each end, imposed its own restrictions. If Narcissus and his reflection — plus a symbolically helpful (though in Ovid's original narrative, entirely absent) cupid — were all to be shown within this constricted space, our self-asorbed hero would have to stand. Comments warmly invited. (Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.) |

Roman

|