- Jaś Elsner, "Introduction".

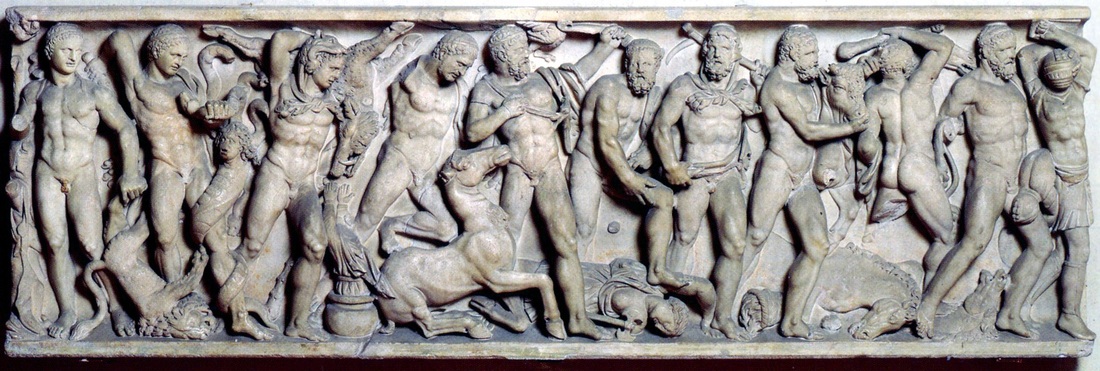

This elaborate Roman sarcophagus is entirely devoted to the Labors of Hercules. Its strategy is to array the twelve episodes in a sequence which stretches across the entire front face of the coffin and wraps around onto the (now missing) ends.

If you’re thinking that this looks oddly familiar, you’re right to wonder. Our previous post looked at another sarcophagus which similarly featured the Labors of Hercules. Here it is again:

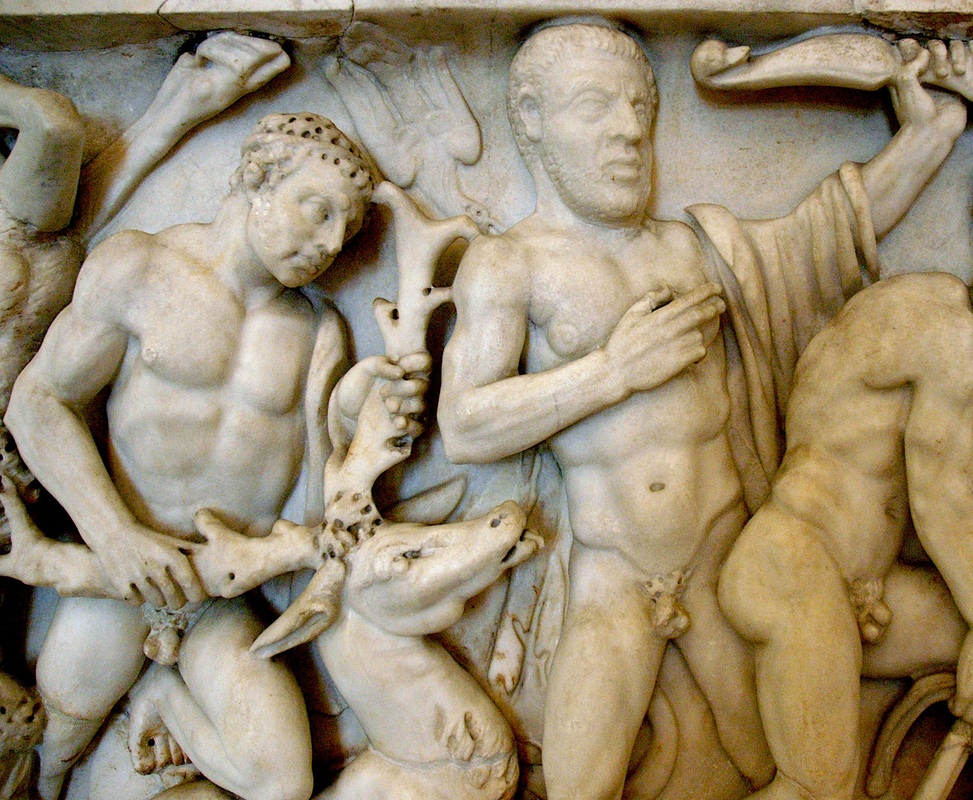

You’ll notice immediately how similar the compositions are. Sure, there are minor differences: the head and torso of the Hydra on today’s piece (second episode from the left) is considerably less monstrous. Eurystheus looks even more ludicrous as he takes refuge in a sunken pithos (a large partially-submerged storage jar) from the Erymanthian Boar slung over Hercules’ shoulder. This sarcophagus gives us two Stymphalian Birds, not one, and neither appears to nibble on Hercules’ bow (instead, one appears to be dive-bombing our hero’s shoulder). And Hippolyta, the Amazon Queen, looks not dead but worrisomely elastic and gumby-like as she spins her head around to look up at her conqueror as he strips her of her girdle. But taken as a whole, these compositions are almost identical.

Was the carver of the second sarcophagus (today’s piece) simply copying the composition of the first directly? It seems unlikely. Some 70 to 80 years separate these two pieces. And the first would almost surely have been in a private family tomb — i.e., not displayed in some public place where other artists might have seen (and copied) it. It turns out that these two more-or-less identical pieces are hardly unique in their copy-cat-dom. Numerous sarcophagi feature the adventures of Orestes, for example, laid out in exactly (or almost exactly) the same way every time. The same holds for sarcophagi staging the murderous story of Medea, the Hunt of the Calydonian Boar, and numerous other myths. They are our best evidence for what was clearly a widespread practice among Roman sculptors: the reliance on so-called pattern books, or copy books: picture books featuring drawings of popular compositions, which carvers could refer to for inspiration as they translated them into stone. Why bother developing one’s own novel composition — and risk months of wasted labor and material if it failed — when one could simply adopt a well-known composition guaranteed to work? Something else you’ve doubtless noticed: the head of the middle Hercules on today's piece — the one shooting the Stymphalian Birds — looks substantially different from the others. That’s because it’s a portrait: a portrait of the deceased man interred within the sarcophagus itself. It may strike us as odd, to see the portrait head of a rather grumpy looking middle-aged Roman man plopped atop the idealized body of Hercules. But it was common Roman practice on sarcophagi between roughly 220 and 250 AD. The Greek mythological imagery on sarcophagi was intended, as a rule, to be applied to the dead Romans buried inside them. Equipping these mythological characters with portrait features of the deceased was a way to make the metaphorical connection between them emphatic: it demanded that the viewer read the mortal through the mythic, and the mythic through the mortal. Which brings us back to the epic saga of facial hair. Hercules on these sarcophagi begins his labors clean-shaven, and develops a beard along the way. We noted last time that it was a strategy for rendering, within the static and immobile terms of stone, the passage of time: a reminder that Hercules’ labors stretched over years. But now, goaded by the portrait to read this dead Roman in terms of the Greek hero, we realize that this device serves an additional purpose. It invites the viewer to imagine the entire adult life of the deceased man — from beardless youth to bearded age — as a single lifelong string of glorious labors and deeds, just like Hercules’. Bombastic? Absolutely. But effective.

Comments warmly invited.

(Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.)

The portraits of the deceased husband and wife who inhabited this Roman sarcophagus were never finished: their faces are blank. That's not very unusual, actually. What is unusual are the mushroom-like lumps poking out just underneath the busts. What are those things?

They must be the couple's preliminary and uncarved hands. But note that while these haven't yet been chiselled, they have been drilled: the perfectly round drill holes are unmistakable. This provides insight into the order of operations of a typical Roman workshop. The drill was used first, for initial indexing (in this case, to index the separation of the fingers). Only after this did the sculptor plan to turn to the chisel for further differentiation of the digits. This particular sarcophagus, however, was pressed into service before he had time to complete that next step — ensuring that our dead couple would remain not only faceless, but forever fingerless. EDIT: I have since been informed that what I took to be uncarved hands are more likely acanthus leaves, for which a handful of other pieces provide precedent. This must surely be right. Also notable is the vignette directly underneath the central tondo. It shows a marvelous bucolic scene: a seated shepherd helps a ewe give birth (!). James Herriot would be proud. But in a funerary context this motif would have carried extra resonance: the imminent birth of a lamb stands in counterpoise to the deceased couple directly above, insisting on life's continuity in the face of death.

Comments warmly invited.

(Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.) |

Roman

|