At least three sarcophagi — one Roman specimen, joined by two Etruscan terracotta pieces featuring kline portraits — were among thousands of archaeological artifacts recently repatriated to Rome from Geneva's Freeport warehouse complex, as reported by the Guardian. Uncovered by a sting operation in 2014, the artifacts, filling 45 crates and reportedly worth some 9 million Euros (although one wonders on what the valuation is based...), where retrieved from the storage unit of Robin Symes, a notorious dealer in illegal antiquities who smuggled the objects, stolen from south Italian digs in the 1970s and 1980s, into Geneva decades ago. Berlin's gorgeous Bode Museum has launched itself online. Virtual visitors can now navigate at will through a full 360º panoramic tour of the entire museum, complete with clickable objects.

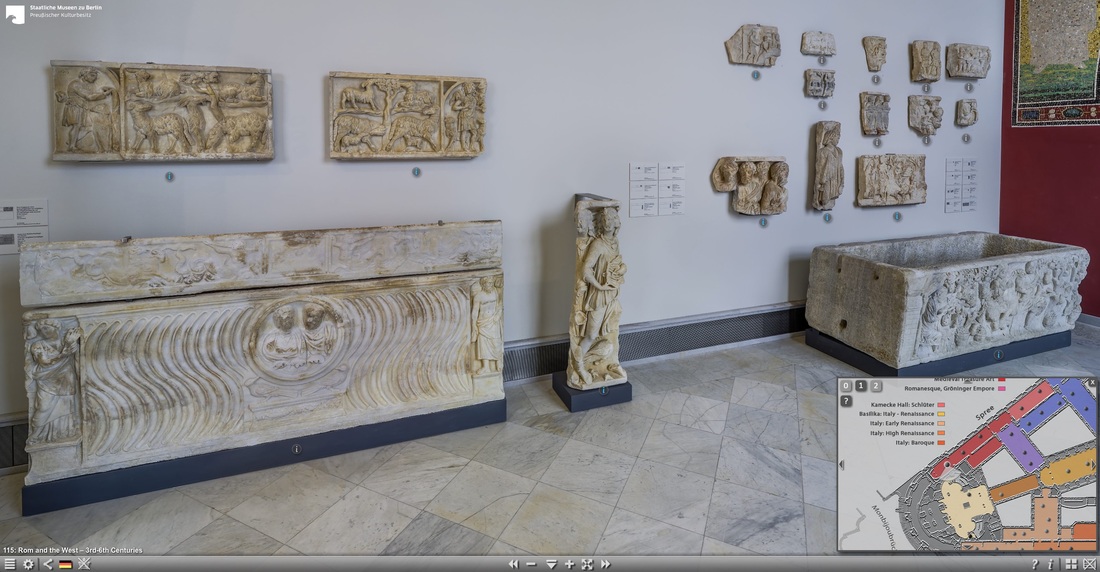

This panoramic tour includes room 115, the sarcophagus room, offering a nice assemblage of late 3rd- and early 4th-century metropolitan specimens. Some, but not all, of these feature early Christian imagery — the reason, one suspects, that they were purchased for the museum's 'Byzantine' collection in the first place. Standouts include:

Below is a still screenshot taken from the virtual tour. Click on it to explore the room and objects yourself. Israel's Haaretz reports the discovery of a Roman sarcophagus at Ashkelon by building contractors who, fearing delays in their construction of luxury villas if its existence were reported to the authorities, instead decided to conceal it. Using a tractor to pull it from the ground — in the process scarring the stone and damaging the relief on multiple sides — they then poured a concrete floor over the findspot to efface any signs of excavation, and hid the sarcophagus beneath a stack of boards and sheet metal. (Additional details here and here.) With a length of 2.5 meters (8.2 feet), this is a massive piece. The lid features a portrait of the deceased shown reclining: not in itself unusual, were it not for the hollow eyes, clearly originally inlaid. This, several other decorative idiosyncrasies, and the fact that the coffin is carved from limestone rather than marble all point to a local product.

- Jaś Elsner, "Introduction".

A previous post featured the mysterious case of the phantom ponytail — a Roman sarcophagus whose occupant, portrayed on the front, appeared to be sprouting phantasmic locks of hair from above his ear. I return to this marvelous piece because a recent trip to Rome has provided me with better photographs (above). These show the marks of recutting, and the ghostly traces of the prior owner's ponytail, in better light. Several readers asked me about the hairstyle of Isis's son Harpocrates, the mythic child whose coiffure was adopted by male devotees of Isis (including this coffin's original owner). Below is a photograph of a bronze statue of the wee god, now in San Francisco's Legion of Honor. Dated to the early 3rd century, it's roughly contemporaneous with our sarcophagus. You can't miss the prominent sidelock. Comments warmly invited. (Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.)

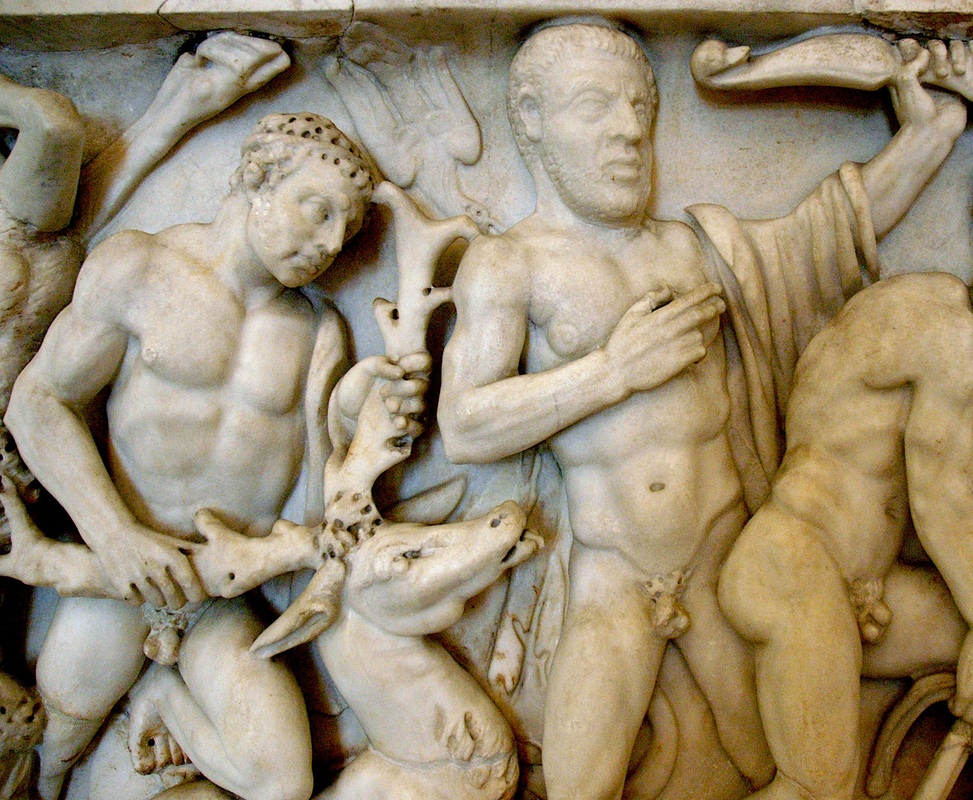

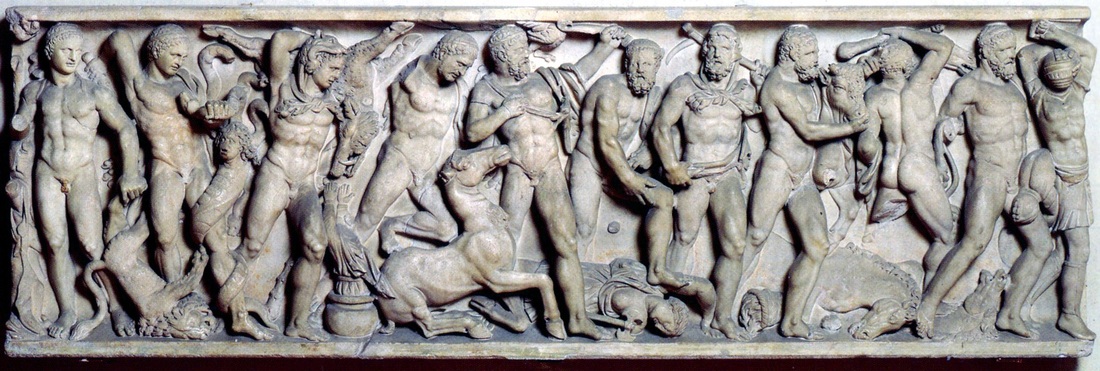

This elaborate Roman sarcophagus is entirely devoted to the Labors of Hercules. Its strategy is to array the twelve episodes in a sequence which stretches across the entire front face of the coffin and wraps around onto the (now missing) ends.

If you’re thinking that this looks oddly familiar, you’re right to wonder. Our previous post looked at another sarcophagus which similarly featured the Labors of Hercules. Here it is again:

You’ll notice immediately how similar the compositions are. Sure, there are minor differences: the head and torso of the Hydra on today’s piece (second episode from the left) is considerably less monstrous. Eurystheus looks even more ludicrous as he takes refuge in a sunken pithos (a large partially-submerged storage jar) from the Erymanthian Boar slung over Hercules’ shoulder. This sarcophagus gives us two Stymphalian Birds, not one, and neither appears to nibble on Hercules’ bow (instead, one appears to be dive-bombing our hero’s shoulder). And Hippolyta, the Amazon Queen, looks not dead but worrisomely elastic and gumby-like as she spins her head around to look up at her conqueror as he strips her of her girdle. But taken as a whole, these compositions are almost identical.

Was the carver of the second sarcophagus (today’s piece) simply copying the composition of the first directly? It seems unlikely. Some 70 to 80 years separate these two pieces. And the first would almost surely have been in a private family tomb — i.e., not displayed in some public place where other artists might have seen (and copied) it. It turns out that these two more-or-less identical pieces are hardly unique in their copy-cat-dom. Numerous sarcophagi feature the adventures of Orestes, for example, laid out in exactly (or almost exactly) the same way every time. The same holds for sarcophagi staging the murderous story of Medea, the Hunt of the Calydonian Boar, and numerous other myths. They are our best evidence for what was clearly a widespread practice among Roman sculptors: the reliance on so-called pattern books, or copy books: picture books featuring drawings of popular compositions, which carvers could refer to for inspiration as they translated them into stone. Why bother developing one’s own novel composition — and risk months of wasted labor and material if it failed — when one could simply adopt a well-known composition guaranteed to work? Something else you’ve doubtless noticed: the head of the middle Hercules on today's piece — the one shooting the Stymphalian Birds — looks substantially different from the others. That’s because it’s a portrait: a portrait of the deceased man interred within the sarcophagus itself. It may strike us as odd, to see the portrait head of a rather grumpy looking middle-aged Roman man plopped atop the idealized body of Hercules. But it was common Roman practice on sarcophagi between roughly 220 and 250 AD. The Greek mythological imagery on sarcophagi was intended, as a rule, to be applied to the dead Romans buried inside them. Equipping these mythological characters with portrait features of the deceased was a way to make the metaphorical connection between them emphatic: it demanded that the viewer read the mortal through the mythic, and the mythic through the mortal. Which brings us back to the epic saga of facial hair. Hercules on these sarcophagi begins his labors clean-shaven, and develops a beard along the way. We noted last time that it was a strategy for rendering, within the static and immobile terms of stone, the passage of time: a reminder that Hercules’ labors stretched over years. But now, goaded by the portrait to read this dead Roman in terms of the Greek hero, we realize that this device serves an additional purpose. It invites the viewer to imagine the entire adult life of the deceased man — from beardless youth to bearded age — as a single lifelong string of glorious labors and deeds, just like Hercules’. Bombastic? Absolutely. But effective.

Comments warmly invited.

(Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.) An earlier post ("Shouldering Responsibility for Recutting") was devoted to a child's sarcophagus with several unusual features. One of them had to do with the child's clothing: she (turned into a portrait of a he) was portrayed wearing sensual off-the-shoulder drapery. Such suggestive garb would be unexpected even for a grown woman: unless she was adopting the guise of Venus, no respectable Roman woman would show herself (un)clad in this way. It would seem an even odder choice for a child. Yet the small dimensions of the coffin left no doubt that it was intended for a child, or at least a juvenile. I filed it away mentally as yet another unique specimen, one of the hundreds of quirky pieces that make the study of Roman sarcophagi endlessly alluring. But it turns out that, while quirky, this feature isn't unique. A colleague has brought another specimen to my attention — from, in fact, the same museum. (The Vatican's collections stretch for halls and halls....) This one, shown above, features a festive procession (in ancient Greek, a thiasos) of various marine creatures: sea nymphs, sea centaurs, dolphins, and, at the far ends, pendant vignettes showing Europa's watery abduction at the hands (horns?) of Zeus in bull's form. The two sea centaurs in the center bear a clipeus medallion framing a portrait of the deceased. As so often, the portrait itself is unfinished: the facial features are still blank, waiting for the final customization once a customer had been found. But the rest of the bust has already been executed — and it clearly shows the same revealing off-the-shoulder drapery as our other piece. Finally, this coffin too was intended for a juvenile: its dimensions are too small for an adult. What's the deal with the sexy kids? I don't have an answer yet — only the beginnings of a pattern. I can't help but wonder, though, whether these pieces were intended for girls who died close to the age of marriage (as young as 12 years for aristocratic girls), their revealing garb meant to underscore the poignancy of a life cut down before its beauty could find adult consummation.

Comments warmly invited.

(Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.) The small dimensions of this piece reveal that it was intended for a child. Given the high rates of infant and juvenile mortality in the ancient world (as in most pre-industrial societies), it is perhaps no surprise that many Roman sarcophagi were carved for children. The sheer number of such pieces is, nonetheless, poignant. The portrait was clearly reworked in antiquity itself: originally intended to depict a young woman or girl, it was recarved to portray a (rather strikingly ugly) boy. That's not especially unusual: as we've already seen, recutting of portraits for reuse by other inhabitants was a common practice, and could even involve sex-changes along the way, as here. What is unusual here is our diminutive subject's off-the-shoulder drapery. It's so suggestive that one might wonder whether the original figure was meant to show Venus, or rather a woman in the guise of Venus. But while the occasional Roman matron was indeed portrayed in the costume and pose of the goddess — a form of mythological portraiture — such mythological portraiture, as far as I know, is never found inside the frame of a tondo/medallion (the Romans called it a clipeus, their word for 'shield', because of its round shape). When Romans equip themselves with the attributes of gods or heroes on sarcophagi, it's always as a full-body figure within a narrative frieze, not a bust isolated within a clipeus. But without the excuse of mythological trappings, what respectable Roman female would choose commemoration in such sexy garb? That it features on a child's sarcophagus makes things even more puzzling. On a different note... the motif of two fowl pecking the ground under the clipeus was clearly a stock vignette, as this piece shows. Comments warmly invited. (Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.) Why does this young man appear to be sprouting phantasmic locks of hair from above his left ear? It seems that he's shadowed by the ghostly ponytail of the coffin's previous owner. The portrait has clearly been recut, and the original must have showed a boy devoted to the goddess Isis: her young male followers proclaimed their devotion by shaving their heads, razoring off everything except a single long tuft of hair above the ear. (The hairstyle was modelled on that of the mythic child Harpocrates, son of Isis.) Sheer need must have driven the later family to choose this piece — with its prior owner's prominently protruding hairstyle — for reappropration and recutting. Why not choose one with a portrait of a non-devotee, whose hair would be much less troublesome to erase? Or else simply make better use of abrasives to take down the background plane around the head, fully scrubbing off any lingering halo? Clearly money — or time — was limited, and the family made do with the used piece they had at hand: a striking reminder of the exigencies of death, the high rates of infant mortality in the ancient world, and above all, the frequent recarving and reuse of sarcophagi in antiquity by Romans themselves. ADDENDUM I return to this piece in a later post: The Phantom Ponytail returns. Comments warmly invited. (Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.) Who is that boy who stands languidly with arms atop his head, doing his best impression of a male pin-up on both ends of this sarcophagus? And why is there a cupid at his feet, pointing to what looks like a theater mask on the ground? If he weren't doubled up, you might think he was Dionysus, or even Apollo, given the youthful features and the erotic posturing. But since he's duplicated, he probably doesn't represent a deity: Roman carvers often duplicated generic figures, and sometimes even mythological mortals; but they usually refrained from doubling up a god. So who is he? The answer: Narcissus. He's very uncommon: out of roughly 15,000 surviving Roman sarcophagi, only 5 (!) show Narcissus. But this is he. The cupid — that wee godling of desire — who stands at his feet is pointing not to a theater mask, but to Narcissus's own reflection. Which Narcissus, of course, is admiring: the erotic nature of his pose reflects his response to his own image. The composition seems bizarre to us: doesn't the Narcissus of Ovid's story (Metamorphoses 3:402-436) bend over the pool, or rather, lie beside it, rather than stand erect over it? Indeed he does. But the formal parameters of this particular format of sarcophagus, which left a tall but narrow field for mythological depiction at each end, imposed its own restrictions. If Narcissus and his reflection — plus a symbolically helpful (though in Ovid's original narrative, entirely absent) cupid — were all to be shown within this constricted space, our self-asorbed hero would have to stand. Comments warmly invited. (Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.)

The portraits of the deceased husband and wife who inhabited this Roman sarcophagus were never finished: their faces are blank. That's not very unusual, actually. What is unusual are the mushroom-like lumps poking out just underneath the busts. What are those things?

They must be the couple's preliminary and uncarved hands. But note that while these haven't yet been chiselled, they have been drilled: the perfectly round drill holes are unmistakable. This provides insight into the order of operations of a typical Roman workshop. The drill was used first, for initial indexing (in this case, to index the separation of the fingers). Only after this did the sculptor plan to turn to the chisel for further differentiation of the digits. This particular sarcophagus, however, was pressed into service before he had time to complete that next step — ensuring that our dead couple would remain not only faceless, but forever fingerless. EDIT: I have since been informed that what I took to be uncarved hands are more likely acanthus leaves, for which a handful of other pieces provide precedent. This must surely be right. Also notable is the vignette directly underneath the central tondo. It shows a marvelous bucolic scene: a seated shepherd helps a ewe give birth (!). James Herriot would be proud. But in a funerary context this motif would have carried extra resonance: the imminent birth of a lamb stands in counterpoise to the deceased couple directly above, insisting on life's continuity in the face of death.

Comments warmly invited.

(Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.) |

Roman

|