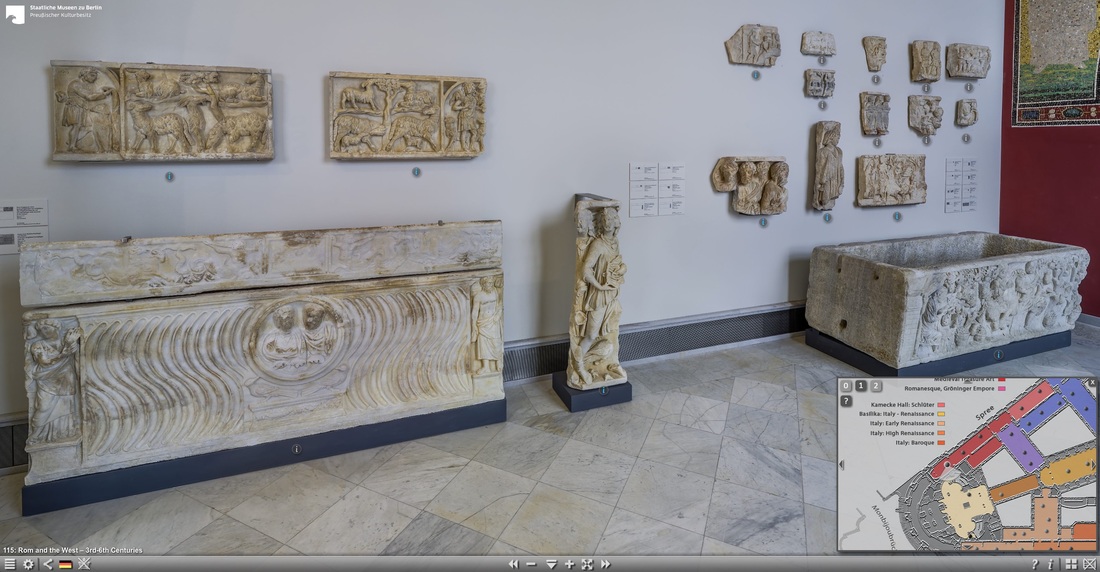

Berlin's gorgeous Bode Museum has launched itself online. Virtual visitors can now navigate at will through a full 360º panoramic tour of the entire museum, complete with clickable objects.

This panoramic tour includes room 115, the sarcophagus room, offering a nice assemblage of late 3rd- and early 4th-century metropolitan specimens. Some, but not all, of these feature early Christian imagery — the reason, one suspects, that they were purchased for the museum's 'Byzantine' collection in the first place. Standouts include:

Below is a still screenshot taken from the virtual tour. Click on it to explore the room and objects yourself.

Why does this sarcophagus have rounded ends? Why the lions' heads, and why are they chomping on rings? Because — and you'll probably think this kooky — this sarcophagus is carved in the shape of a wooden wine vat. The rounded ends are characteristic of the large tubs in which Romans pressed grapes to make wine. More importantly, so are the lions: we know from ancient depictions of actual Roman wine troughs that they often carried fancy felines' heads, carved in relief near the ends of the vat. These served as elaborate (and humorous) decoration for the spigots (!) installed in their mouths: wine flowed from the ferocious maws of lions — if you dared to put your hand directly between their jaws to open the tap. They met other functional needs as well. The metal rings used as handles for hoisting and dragging the vat had to be embedded in something; and ideally that something would project outward from the rest of the tub, to make carrying easier. These leonine bosses thus served as anchors for carrying handles ("Think you can handle a lion? Now you can!") as well as fanciful frames for spigots. Here the form of one of those elaborate wine tubs has been translated into stone, to hold very different contents. This was a popular format for sarcophagi: many elite Romans commissioned this style of coffin, particularly during the third century. Just imagine a wealthy businessman or an important Senator choosing a stone-imitation wine vat as his vessel for eternity. This would be unthinkable for us. But it was entirely unproblematic for Romans, who so often — unlike us — preferred to meet death with humor. As a side note.... you'll observe that the marble from which this sarcophagus was carved has several bands of darker color that run through the stone. There's a wide, very dark band near the bottom; and a set of lighter, blue-gray bands that run across the top. That's a characteristic feature of marble quarried on the island of Proconnesus (now Marmara), not too far from Istanbul, in modern-day Turkey. It was a popular choice of stone for Roman sarcophagi in the third century. You might think it an odd choice, given how far Proconnesus is from Rome. But transport by sea was far easier and faster than transport over land in antiquity. And the quarries on the island were close to the water — unlike the quarries of Italy. As a result, shipping marble all the way from Turkey to Rome was actually cheaper than using marble from Italy itself. Comments warmly invited. (Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.) Who is that boy who stands languidly with arms atop his head, doing his best impression of a male pin-up on both ends of this sarcophagus? And why is there a cupid at his feet, pointing to what looks like a theater mask on the ground? If he weren't doubled up, you might think he was Dionysus, or even Apollo, given the youthful features and the erotic posturing. But since he's duplicated, he probably doesn't represent a deity: Roman carvers often duplicated generic figures, and sometimes even mythological mortals; but they usually refrained from doubling up a god. So who is he? The answer: Narcissus. He's very uncommon: out of roughly 15,000 surviving Roman sarcophagi, only 5 (!) show Narcissus. But this is he. The cupid — that wee godling of desire — who stands at his feet is pointing not to a theater mask, but to Narcissus's own reflection. Which Narcissus, of course, is admiring: the erotic nature of his pose reflects his response to his own image. The composition seems bizarre to us: doesn't the Narcissus of Ovid's story (Metamorphoses 3:402-436) bend over the pool, or rather, lie beside it, rather than stand erect over it? Indeed he does. But the formal parameters of this particular format of sarcophagus, which left a tall but narrow field for mythological depiction at each end, imposed its own restrictions. If Narcissus and his reflection — plus a symbolically helpful (though in Ovid's original narrative, entirely absent) cupid — were all to be shown within this constricted space, our self-asorbed hero would have to stand. Comments warmly invited. (Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.)

The portraits of the deceased husband and wife who inhabited this Roman sarcophagus were never finished: their faces are blank. That's not very unusual, actually. What is unusual are the mushroom-like lumps poking out just underneath the busts. What are those things?

They must be the couple's preliminary and uncarved hands. But note that while these haven't yet been chiselled, they have been drilled: the perfectly round drill holes are unmistakable. This provides insight into the order of operations of a typical Roman workshop. The drill was used first, for initial indexing (in this case, to index the separation of the fingers). Only after this did the sculptor plan to turn to the chisel for further differentiation of the digits. This particular sarcophagus, however, was pressed into service before he had time to complete that next step — ensuring that our dead couple would remain not only faceless, but forever fingerless. EDIT: I have since been informed that what I took to be uncarved hands are more likely acanthus leaves, for which a handful of other pieces provide precedent. This must surely be right. Also notable is the vignette directly underneath the central tondo. It shows a marvelous bucolic scene: a seated shepherd helps a ewe give birth (!). James Herriot would be proud. But in a funerary context this motif would have carried extra resonance: the imminent birth of a lamb stands in counterpoise to the deceased couple directly above, insisting on life's continuity in the face of death.

Comments warmly invited.

(Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.) |

Roman

|