|

Sarah Madole, of CUNY, will be giving a paper at the upcoming 2018 Annual Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America.

The title: "Roman Sarcophagi with Catacomb Contexts: A Case Study". The paper will be delivered in Session 1J — New Approaches to the Catacombs of Rome — of which she is also the organizer and Chair. Scheduled for Friday, January 5, 8:00 - 10:30 am, the session also features papers by Nicola Denzey Lewis, Jenny Kreiger, Daniel Ullucci, and Jessica dello Russo, with concluding response/discussion by the formidable John Bodel. Not to be missed.

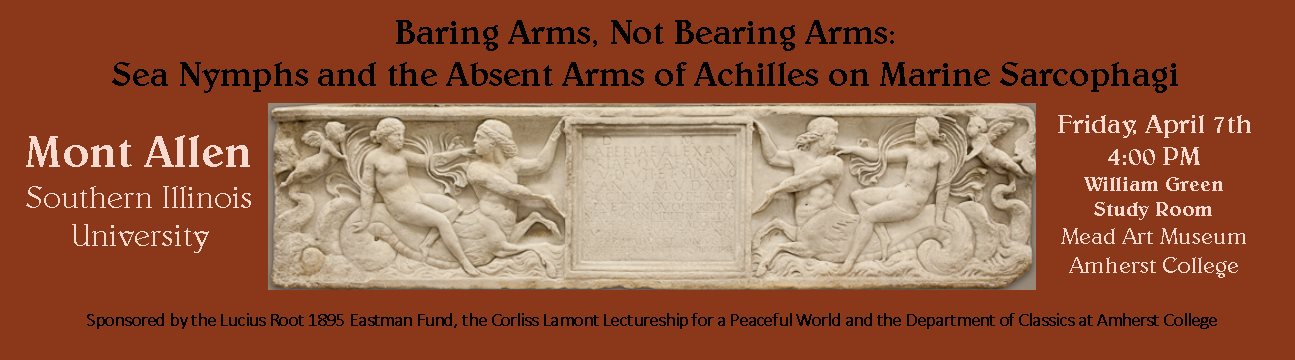

As just reported by the BBC, a Roman sarcophagus was uncovered last month at a construction site on Swan Street, near Borough Market, in central London. It was found within a fourth-century mausoleum occupying prime real estate: directly beside the main road into the city, always the most desirable location in any Roman town's funerary landscape. The sarcophagus itself — only the second such ever discovered in London — has not yet been fully freed from the dirt, so its decoration is yet unknown. Initial tests with a metal detector, however, indicate the presence of small metal objects within, raising hopes that some grave goods may have survived. On Friday, April 7, the author of this blog will give a lecture at Amherst College on a gorgeous — and gorgeously idiosyncratic — marine sarcophagus recently acquired by Amherst's Mead Art Museum. All are welcome.

As reported by The Daily Mail, The BBC, The Telegraph, and The New York Times, among others, a Roman sarcophagus (or at least, the front slab of one) has been discovered on the grounds of Blenheim Palace, where it has spent the last century in service as a tulip planter. This lenoid piece (a coffin shaped like a lenos: a wine vat) features the lions-head bosses typical for this shape, while the figural frieze itself — a Dionysiac scene of the inebriated god approaching the sleeping form of his beloved Ariadne, her own pose echoed by that of Hercules reclining boozily at left (an unusual addition) — plays on the lenos's associations with wine. The dates reported for the piece are a mess. Most of the sources above describe it as "dating back to A.D. 300" or "300 AD" — but then go on to quote spokesmen who place the carving in the 2nd century (i.e., well over a century earlier), with no notice of the resulting chronological inconsistency. In truth, neither set of reported dates can be correct. AD 300 is far too late for this work. But the 2nd century is just as clearly too early, as an eye to the carving technique reveals. (Just look at the drill-heavy treatment of the lions' manes.) A 3rd-century date, tilting earlier rather than later — the 220s AD, or perhaps even the 230s — seems most likely. A wee plug here. The upcoming 2017 Annual Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America — convening this January 5-8 in Toronto — features an organized session devoted entirely to Roman sarcophagi. With six papers and two respondents (among them Ortwin Dally, Director of the DAI-Rome), it offers a full lineup of sarcophagine (sarcophagal? sarcophagoidal?) delight.

Session 6I: New Research on Roman Sarcophagi: Eastern, Western, Christian Saturday, Jan. 7, 1:45 - 4:45 pm Chairs: Sarah Madole (CUNY—BMCC) and Mont Allen (Southern Illinois University) (1) "Sarcophagus Studies: The State of the Field (as I see it)" Bjoern C. Ewald (Universit of Toronto) (2) "Roman Sarcophagi from Dokimeion in Asia Minor: Conceptual Differences between Rome and Athens" Esen Öğüş (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich) (3) "A New Mythological Sarcophagus at Aphrodisias" Heather N. Turnbow (The Catholic University of America) (4) "Beyond Grief: A Mother's Tears and Representations of Semele and Niobe on Roman Sarcophagi" Sarah Madole (CUNY—BMCC) (5) "Strutting Your Stuff: Finger Struts on Roman Sarcophagi" Mont Allen (Southern Illinois University) (6) "Love and Death: Jonah as Endymion in Early Christian Art" Robert Couzin (independent scholar) (7) Response Christopher H. Hallett (U.C. Berkeley) (8) Response Ortwin Dally (Deutsches Archäologisches Institut)

National Museum of Beirut reopens basement featuring 31 anthropoid sarcophagi, Icarus sarcophagus12/6/2016 This is one of the most heart-warming developments that I've ever had the pleasure of blogging.

Abu Dhabi's The National reports that the National Museum of Beirut has — after 41 years of closure following the outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War in 1975 — reopened its basement galleries. Finding itself directly on the infamous Green Line that bisected Beirut during the Civil War, the museum and its objects were immediately imperiled by civil strife and looting. Read the full report in The National of the extreme measures to which then director of antiquities Maurice Chehab went in order to safeguard the collection in the basement. The story is astonishing. The highlight of the collection is the world's largest series of anthropoid sarcophagi: 31 in all, all from Phoenician Sidon and carved between the 6th and 4th centuries BC. Also figuring prominently in the reopened galleries is a fragment of a Roman sarcophagus from Beirut itself depicting Icarus standing beside the wing-crafting Daedalus, according to the Daily Mail. The scene is fantastically rare: I know of no other Roman sarcophagus that shows it. Istanbul's Daily Sabah reports that yet another Roman sarcophagus has been discovered in Turkey's Hisardere district, five kilometers northeast of İznik, less than a year after the discovery of this piece in the same district.

The İznik Museum, it is related, plans to put the specimen on display. At least three sarcophagi — one Roman specimen, joined by two Etruscan terracotta pieces featuring kline portraits — were among thousands of archaeological artifacts recently repatriated to Rome from Geneva's Freeport warehouse complex, as reported by the Guardian. Uncovered by a sting operation in 2014, the artifacts, filling 45 crates and reportedly worth some 9 million Euros (although one wonders on what the valuation is based...), where retrieved from the storage unit of Robin Symes, a notorious dealer in illegal antiquities who smuggled the objects, stolen from south Italian digs in the 1970s and 1980s, into Geneva decades ago. As originally reported by Today's Zaman (no longer available) and reposted by News Network: Archaeology: in November of last year a Roman sarcophagus was unearthed by a farmer in the Hisardere area of Turkey, northeast of İznik.

The format of the coffin seems typical of those from Docimium/Dokimeion; but Esen Öğüş, a colleague more familiar with eastern sarcophagi than I, tells me she thinks it is actually a local product carved in imitation of the expensive Docimean pieces. She intends to publish the finding.

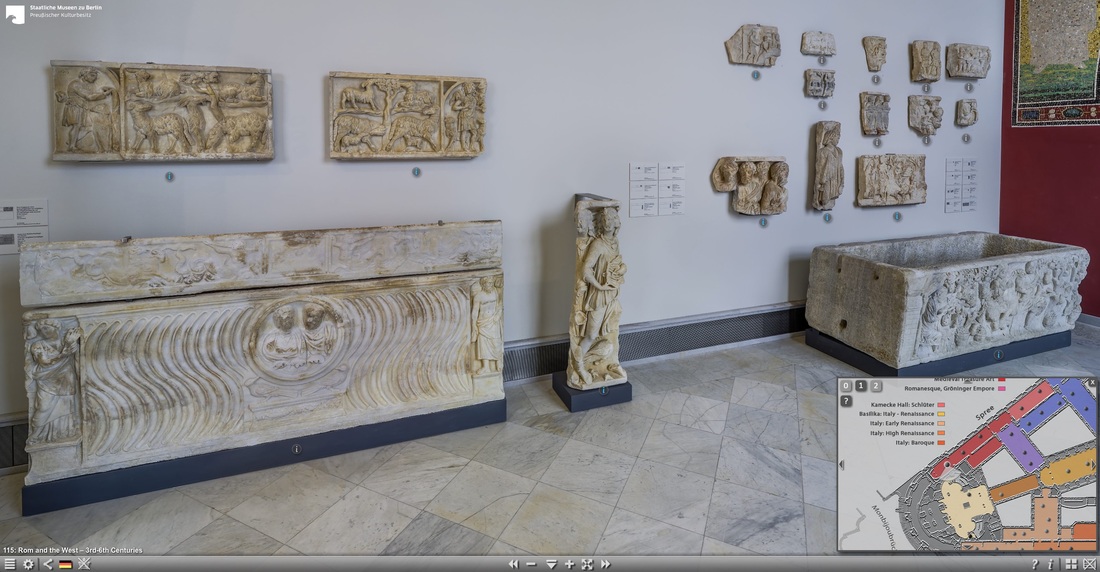

Berlin's gorgeous Bode Museum has launched itself online. Virtual visitors can now navigate at will through a full 360º panoramic tour of the entire museum, complete with clickable objects.

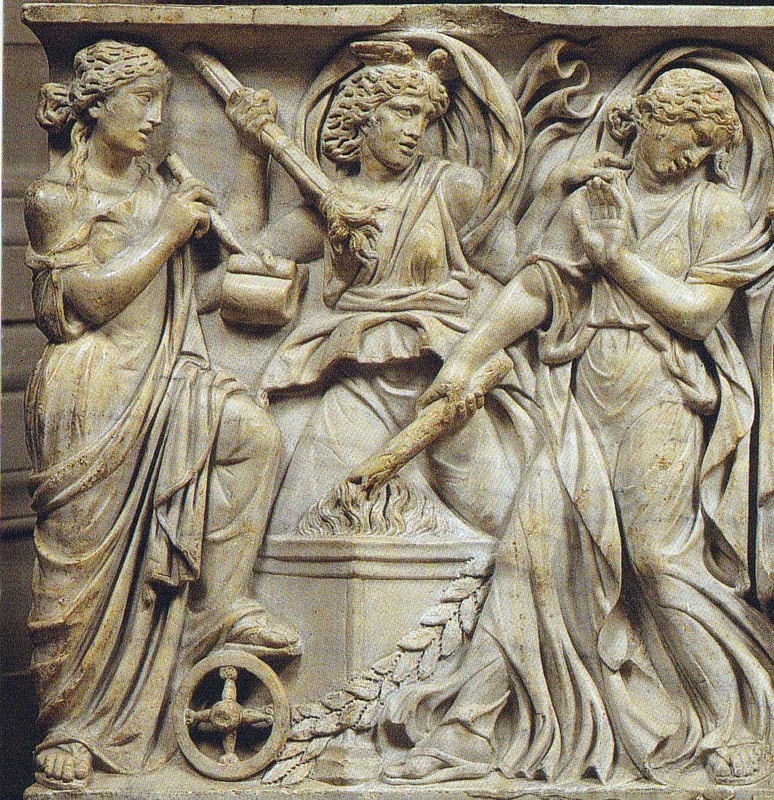

This panoramic tour includes room 115, the sarcophagus room, offering a nice assemblage of late 3rd- and early 4th-century metropolitan specimens. Some, but not all, of these feature early Christian imagery — the reason, one suspects, that they were purchased for the museum's 'Byzantine' collection in the first place. Standouts include:

Below is a still screenshot taken from the virtual tour. Click on it to explore the room and objects yourself.

three conference papers on ancient sarcophagi (2016 AIA Annual Meeting, San Francisco, Jan. 6-9)12/15/2015 A bonanza. The upcoming 2016 Annual Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America (San Francisco, January 6-9) features three papers on ancient sarcophagi:

"Aphrodisian Sarcophagus Sculptors Abroad?" Sarah Madole, CUNY-BMCC (session 1H) "Who Bought Bucolic? Sheep, Cows, and Villas on Roman Sarcophagi" Mont Allen, Southern Illinois University (session 1H) "Local History, Lasting Legacy: The 'Alexander' Sarcophagus in Context" Rachel Spradley, Southern Methodist University (session 5G)

As detailed by Artlyst, London's Ordovas gallery is exhibiting a collection of works on marine themes. Titled The Big Blue, it features a fragment of an Antonine marine sarcophagus showing a Nereid and Tritons (visible at the far right in the photos below), beside works by Francis Bacon, Gustave Courbet, Max Ernst, Pablo Picasso, Piet Mondrian, Yves Klein, Damien Hirst, and others. Although one wonders about the provenance of the piece, it is lovely to see a Roman sarcophagus celebrated for its relevance amidst such famous modern company. The show remains on display until December 12. As reported by the Tribune de Genève — and later covered in greater detail by the Tages-Anzeiger (many thanks to Christian Russenberger for the link) — a Swiss public prosecutor has ordered that a Roman sarcophagus deposited in the Geneva Freeport warehouse in 2010 and subsequently seized by Swiss Customs during an inventory check later that year be returned to Turkey. The piece itself is exquisite: a creamy Docimean specimen, likely Antonine in date, showing the Twelve Labors of Hercules. As detailed in earlier blog posts (here, here, and here), Metropolitan sarcophagi (i.e., those from the city of Rome itself) devoted to the Labors of Hercules typically array the hero's first ten labors on the front of the chest in narrative order, with the eleventh and twelfth depicted on the short ends, and nothing on the back (as usual for Metropolitan works), This piece, in contrast, strews the vignettes around all four sides — as expected for an eastern product — in no discernable order. Israel's Haaretz reports the discovery of a Roman sarcophagus at Ashkelon by building contractors who, fearing delays in their construction of luxury villas if its existence were reported to the authorities, instead decided to conceal it. Using a tractor to pull it from the ground — in the process scarring the stone and damaging the relief on multiple sides — they then poured a concrete floor over the findspot to efface any signs of excavation, and hid the sarcophagus beneath a stack of boards and sheet metal. (Additional details here and here.) With a length of 2.5 meters (8.2 feet), this is a massive piece. The lid features a portrait of the deceased shown reclining: not in itself unusual, were it not for the hollow eyes, clearly originally inlaid. This, several other decorative idiosyncrasies, and the fact that the coffin is carved from limestone rather than marble all point to a local product. Romania's Nine O'Clock reports the discovery — the first ever — of a Roman sarcophagus at ancient Porolissum, capital of Dacia Porolissensis.

The limestone chest and lid apparently lack adornment and are clearly unfinished. Judging from the lid's four corner acroterial projections and its double-pitched roof, however, the carver was following eastern rather than metropolitan Roman models. This choice might seem a bit unexpected for a Latin-speaking province — but is perhaps less surprising in light of Porolissensis's Transylvanian location and proximity to eastern centers. The large notch cut in the lid, showing signs of discoloration, is intriguing. Perhaps a sign of reuse? Reuse might also account for the coffin's unusual find spot: not in the town's necropolis outside the Roman castrum, but rather "within the sacred area". (of Liber Pater? of Nemesis? We're not told.) Lebanon's Daily Star reports the excavation of a Roman sarcophagus, as well as remnants of an ancient well, at a construction site in Sidon's Bustan al-Kabir neighborhood. From the photograph below the sarcophagus appears to be of standard eastern garland type, pressed into service as a blank.

Two burial grounds, yielding skeletons, pottery, and coins with Latin inscriptions, were found at the same site a month ago. The relationship of the sarcophagus and the burials to the well has not yet been clarified.

Istanbul's BGN News reports that Turkish authorities near Izmir recently foiled an attempt by two men to smuggle a Roman child's sarcophagus out of the country in a light commercial vehicle. According to the report, official analysis of the recovered sarcophagus revealed that it had never before been opened. (So what were the contents when the piece was finally uncorked? — we're not told.) It was subsequently delivered to the Directorate of the Izmir Museums. The fuller story is here. That the specimen — from the pictures, a wee piece featuring garlands suspended from rams' heads — is "at least 2,000 years old" seems unlikely. A new article by Esen Öğüş — one of only a handful to address Asian sarcophagi — recently appeared in the AJA. It presents, in accessible form, some of the most important conclusions of her doctoral thesis.

The full reference: Esen Öğüş, "Columnar Sarcophagi from Aphrodisias: Elite Emulation in the Greek East", American Journal of Archaeology 118, no. 1 (January 2014): 113-36. |

Roman

|