|

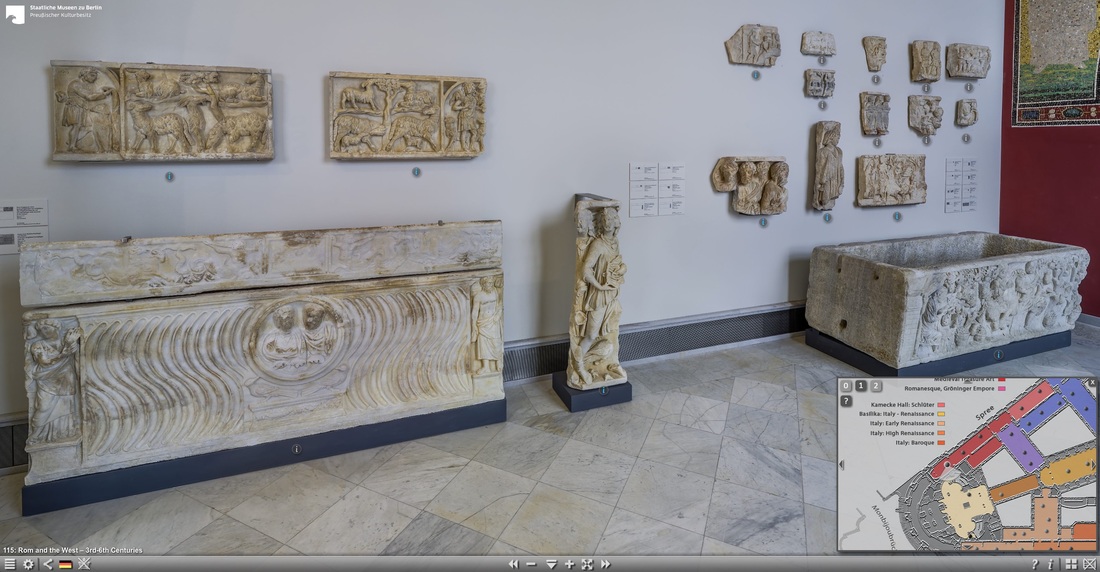

Berlin's gorgeous Bode Museum has launched itself online. Virtual visitors can now navigate at will through a full 360º panoramic tour of the entire museum, complete with clickable objects.

This panoramic tour includes room 115, the sarcophagus room, offering a nice assemblage of late 3rd- and early 4th-century metropolitan specimens. Some, but not all, of these feature early Christian imagery — the reason, one suspects, that they were purchased for the museum's 'Byzantine' collection in the first place. Standouts include:

Below is a still screenshot taken from the virtual tour. Click on it to explore the room and objects yourself.

- Jaś Elsner, "Introduction".

This sarcophagus is centered on the figure of Dionysus, god of wine, shown too intoxicated to stand. A helpful Satyr, a member of the god's debauched retinue, has to prop the tipsy deity up. Flanking Dionysus on both sides are personifications of the four seasons, symbols of plenty and abundance. I feature this piece, however, not for its endearing subject matter, but for its sculptural technique. It illustrates Roman carvers' ever greater reliance on the drill. Although the drill had been employed for working marble as far back as the Archaic period in Greece and was already widely used by the Early Classical period, nothing compared to the popularity it enjoyed in Roman hands, where it was used to render a wide variety of surface effects. This depended on a fundamental change in attitude towards traces of tooling: a willingness among Romans to advertise, rather than hide, tool marks. This stood in marked contrast to earlier practice. Greek sculptors had already employed the drill extensively for carving; but the Archaic and Classical ideal was a final surface devoid of any trace of tooling. Hence sculptors of these periods took obsessive care to efface all such marks, whether of chisel or drill. Hellenistic carvers show greater tolerance for tool marks, and extend this even to the drill, whose traces they often leave. But it is Roman sculptors who purposefully showcase the tool, actively foregrounding its distinctive optical bite. This flashy use of the drill for visual effects on sarcophagi seems to begin a little after the middle of the second century, in the mid-Antonine period. Used very sparingly at first, it was gradually put to ever greater use. By the latter part of the third century its grooves, channels, and isolated bore holes had taken over the carved surface, becoming the main means of rendering optical effects. This was especially the case in the face and hair of figures. As illustration of this artistic mode, consider the sarcophagus here, a piece likely carved during the reign of Constantine. Cast your eyes on the tiny cupid perched on the shoulder of the third season from the left. The detail shot makes things clear: his wee face has been given ‘features’ not through any plastic modeling with the chisel, but by simply drilling six holes into his amorphous blob of a head to index the eyes, nostrils, and the corners of the mouth. You can't help but think that this shouldn't work, because the style produces an utterly unrealistic surface. The real human form is not, after all, pockmarked and beehived with numerous cavernous holes. Yet this seldom strikes the viewer. This is because the drillwork serves as highly effective visual accenting: since the holes are used to emphasize areas where the eye is normally arrested anyway (the genitals, for example, or the eye itself), or features that the eye is normally accustomed to differentiating (such as the point near the knuckles where the fingers separate), its optical effects are often perceived as ‘naturalistic’ — especially at a distance — even though the impossible surface form that it produces is profoundly artificial. Comments warmly invited. (The Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work equally well.) A previous post featured the mysterious case of the phantom ponytail — a Roman sarcophagus whose occupant, portrayed on the front, appeared to be sprouting phantasmic locks of hair from above his ear. I return to this marvelous piece because a recent trip to Rome has provided me with better photographs (above). These show the marks of recutting, and the ghostly traces of the prior owner's ponytail, in better light. Several readers asked me about the hairstyle of Isis's son Harpocrates, the mythic child whose coiffure was adopted by male devotees of Isis (including this coffin's original owner). Below is a photograph of a bronze statue of the wee god, now in San Francisco's Legion of Honor. Dated to the early 3rd century, it's roughly contemporaneous with our sarcophagus. You can't miss the prominent sidelock. Comments warmly invited. (Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.) Why does this young man appear to be sprouting phantasmic locks of hair from above his left ear? It seems that he's shadowed by the ghostly ponytail of the coffin's previous owner. The portrait has clearly been recut, and the original must have showed a boy devoted to the goddess Isis: her young male followers proclaimed their devotion by shaving their heads, razoring off everything except a single long tuft of hair above the ear. (The hairstyle was modelled on that of the mythic child Harpocrates, son of Isis.) Sheer need must have driven the later family to choose this piece — with its prior owner's prominently protruding hairstyle — for reappropration and recutting. Why not choose one with a portrait of a non-devotee, whose hair would be much less troublesome to erase? Or else simply make better use of abrasives to take down the background plane around the head, fully scrubbing off any lingering halo? Clearly money — or time — was limited, and the family made do with the used piece they had at hand: a striking reminder of the exigencies of death, the high rates of infant mortality in the ancient world, and above all, the frequent recarving and reuse of sarcophagi in antiquity by Romans themselves. ADDENDUM I return to this piece in a later post: The Phantom Ponytail returns. Comments warmly invited. (Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.)

The portraits of the deceased husband and wife who inhabited this Roman sarcophagus were never finished: their faces are blank. That's not very unusual, actually. What is unusual are the mushroom-like lumps poking out just underneath the busts. What are those things?

They must be the couple's preliminary and uncarved hands. But note that while these haven't yet been chiselled, they have been drilled: the perfectly round drill holes are unmistakable. This provides insight into the order of operations of a typical Roman workshop. The drill was used first, for initial indexing (in this case, to index the separation of the fingers). Only after this did the sculptor plan to turn to the chisel for further differentiation of the digits. This particular sarcophagus, however, was pressed into service before he had time to complete that next step — ensuring that our dead couple would remain not only faceless, but forever fingerless. EDIT: I have since been informed that what I took to be uncarved hands are more likely acanthus leaves, for which a handful of other pieces provide precedent. This must surely be right. Also notable is the vignette directly underneath the central tondo. It shows a marvelous bucolic scene: a seated shepherd helps a ewe give birth (!). James Herriot would be proud. But in a funerary context this motif would have carried extra resonance: the imminent birth of a lamb stands in counterpoise to the deceased couple directly above, insisting on life's continuity in the face of death.

Comments warmly invited.

(Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.) |

Roman

|