|

Following several years of renovation, the Saint Louis Art Museum's collection of ancient art has recently reopened with a fresh face, thanks to reinstallation by Assistant Curator Lisa Çakmak.

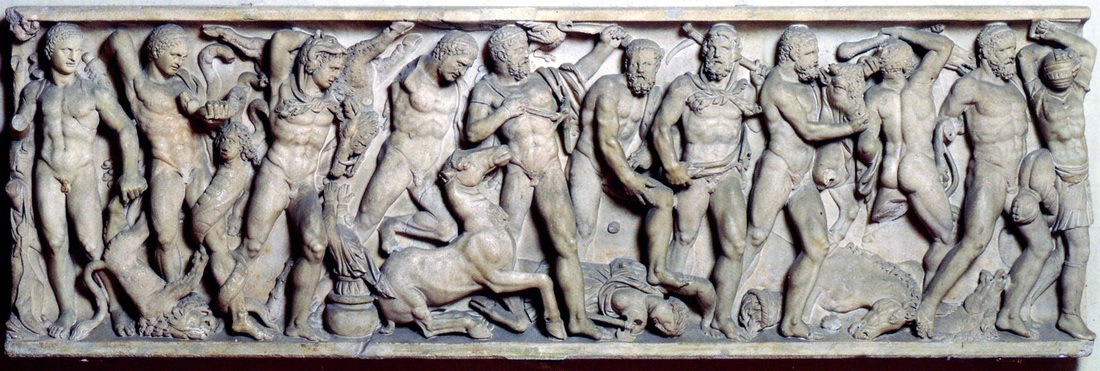

The Roman gallery now prominently features a fragment of a sarcophagus showing the Twelve Labors of Hercules (inv. 138:1987). The proportions of this Antonine fragment — its 1.42 meters must represent less than half of the original length — are absolutely massive. This was a monumental piece indeed. Its composition also departs from the standard in unexpected ways. Most noticeably, our hero here turns his torso to the left rather than right when bludgeoning the Hydra (contrast with the pieces in Mantua and Rome's Palazzo Altemps) — a choice that quirkily interrupts the narrative's rightward flow. To my knowledge, the last 23 years have seen only four (!) American dissertations devoted to Roman sarcophagi. The good news is that all four were filed within the last five years, reflecting surging interest among English-speaking scholars in a field traditionally dominated by German scholarship.

Of these four dissertations, three focus on Asian sarcophagi, taking advantage of the wealth of material unearthed at Roman Aphrodisias. The first, by Esen Öğüş, explores the socio-cultural significance of columnar sarcophagi within both their local Aphrodisian context and broader patterns of burial in Asia Minor. The full reference: Esen Öğüş, Columnar Sarcophagi from Aphrodisias: Construction of Elite Identity in the Greek East, Harvard University, 2010. Abstract (courtesy of the author): This thesis explores the social and cultural meaning of a specific group of marble sarcophagi from Aphrodisias in Caria. The columnar sarcophagi, a corpus of 212 fully preserved or fragmentary pieces, are decorated on chests with projecting columns forming aediculae for the display of standing human figures in relief. Funerary inscriptions inform us that the majority of the Aphrodisian sarcophagi date to the third century A.D. and did not belong to the traditional city elite known from honorary inscriptions in the first two centuries A.D., but to a class of artisans and tradesmen who were newly granted citizenship by Caracalla’s Edict in A.D. 212. Part I of the thesis, drawing evidence from epigraphic analysis, situates the columnar sarcophagi within their archaeological context, and clarifies aspects of sarcophagus use in the city of Aphrodisias. Part II classifies and presents the extant corpus in three groups by highlighting the significance of each. Part III interprets the material within both the local cultural context and the widespread burial culture of Asia Minor. The iconography of the columnar sarcophagi, featuring human figures that exhibit paideia, reflects two sets of influences on the local culture: the ideals of the Second Sophistic; and the honorific habit that commemorated the good deeds of wealthy elite citizens. The overall appearance of a sarcophagus chest resembles a public building with a columnar façade and honorific statues embedded in it. Therefore, by commissioning columnar sarcophagi, the sub-elite patrons owned a personal model of a public building with their small-scale portrait statues on its façade. Since the ownership of a public statue was a privilege that the people of this status never had the chance to enjoy in life, they adapted conventions of private funerary art to avail themselves of a similar privilege in death. Exploring the social meaning of other local groups of sarcophagi in Asia Minor reveals that new citizens elsewhere developed their own local iconography in the third century that centered on their self-presentation and aspirations to elite status.

- Jaś Elsner, "Introduction".

With a new job leaving me less time for sustained musings, accompanied by the acute awareness that there exists no central repository for news concerning Roman sarcophagi, I've decided to expand the focus of this blog. My hope is that it will serve as a venue for announcing all that's new and noteworthy in our burgeoning field.

I hope you, gentle readers, will help make this a collective endeavor. If you come across anything new pertaining to Roman sarcophagi — whether a recent article or book addressing them, an exhibition or website featuring them, or an excavation uncovering them — please do let me know so I can share it here. This sarcophagus is centered on the figure of Dionysus, god of wine, shown too intoxicated to stand. A helpful Satyr, a member of the god's debauched retinue, has to prop the tipsy deity up. Flanking Dionysus on both sides are personifications of the four seasons, symbols of plenty and abundance. I feature this piece, however, not for its endearing subject matter, but for its sculptural technique. It illustrates Roman carvers' ever greater reliance on the drill. Although the drill had been employed for working marble as far back as the Archaic period in Greece and was already widely used by the Early Classical period, nothing compared to the popularity it enjoyed in Roman hands, where it was used to render a wide variety of surface effects. This depended on a fundamental change in attitude towards traces of tooling: a willingness among Romans to advertise, rather than hide, tool marks. This stood in marked contrast to earlier practice. Greek sculptors had already employed the drill extensively for carving; but the Archaic and Classical ideal was a final surface devoid of any trace of tooling. Hence sculptors of these periods took obsessive care to efface all such marks, whether of chisel or drill. Hellenistic carvers show greater tolerance for tool marks, and extend this even to the drill, whose traces they often leave. But it is Roman sculptors who purposefully showcase the tool, actively foregrounding its distinctive optical bite. This flashy use of the drill for visual effects on sarcophagi seems to begin a little after the middle of the second century, in the mid-Antonine period. Used very sparingly at first, it was gradually put to ever greater use. By the latter part of the third century its grooves, channels, and isolated bore holes had taken over the carved surface, becoming the main means of rendering optical effects. This was especially the case in the face and hair of figures. As illustration of this artistic mode, consider the sarcophagus here, a piece likely carved during the reign of Constantine. Cast your eyes on the tiny cupid perched on the shoulder of the third season from the left. The detail shot makes things clear: his wee face has been given ‘features’ not through any plastic modeling with the chisel, but by simply drilling six holes into his amorphous blob of a head to index the eyes, nostrils, and the corners of the mouth. You can't help but think that this shouldn't work, because the style produces an utterly unrealistic surface. The real human form is not, after all, pockmarked and beehived with numerous cavernous holes. Yet this seldom strikes the viewer. This is because the drillwork serves as highly effective visual accenting: since the holes are used to emphasize areas where the eye is normally arrested anyway (the genitals, for example, or the eye itself), or features that the eye is normally accustomed to differentiating (such as the point near the knuckles where the fingers separate), its optical effects are often perceived as ‘naturalistic’ — especially at a distance — even though the impossible surface form that it produces is profoundly artificial. Comments warmly invited. (The Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work equally well.) A previous post featured the mysterious case of the phantom ponytail — a Roman sarcophagus whose occupant, portrayed on the front, appeared to be sprouting phantasmic locks of hair from above his ear. I return to this marvelous piece because a recent trip to Rome has provided me with better photographs (above). These show the marks of recutting, and the ghostly traces of the prior owner's ponytail, in better light. Several readers asked me about the hairstyle of Isis's son Harpocrates, the mythic child whose coiffure was adopted by male devotees of Isis (including this coffin's original owner). Below is a photograph of a bronze statue of the wee god, now in San Francisco's Legion of Honor. Dated to the early 3rd century, it's roughly contemporaneous with our sarcophagus. You can't miss the prominent sidelock. Comments warmly invited. (Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.)

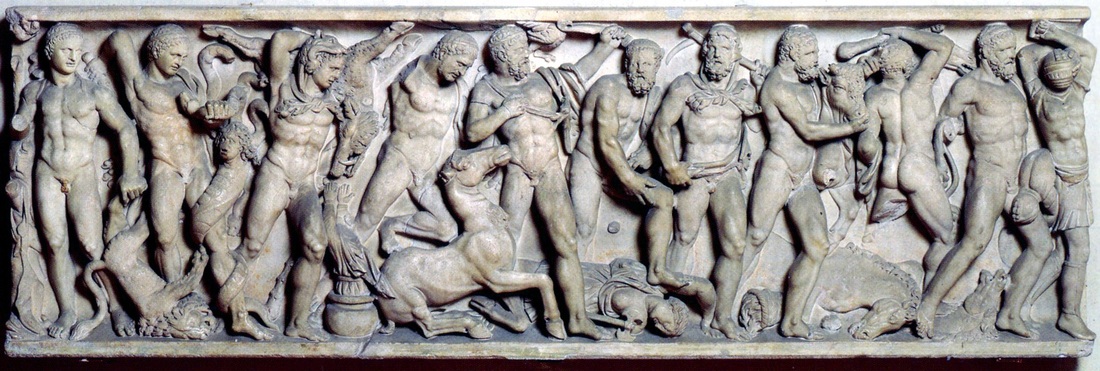

This elaborate Roman sarcophagus is entirely devoted to the Labors of Hercules. Its strategy is to array the twelve episodes in a sequence which stretches across the entire front face of the coffin and wraps around onto the (now missing) ends.

If you’re thinking that this looks oddly familiar, you’re right to wonder. Our previous post looked at another sarcophagus which similarly featured the Labors of Hercules. Here it is again:

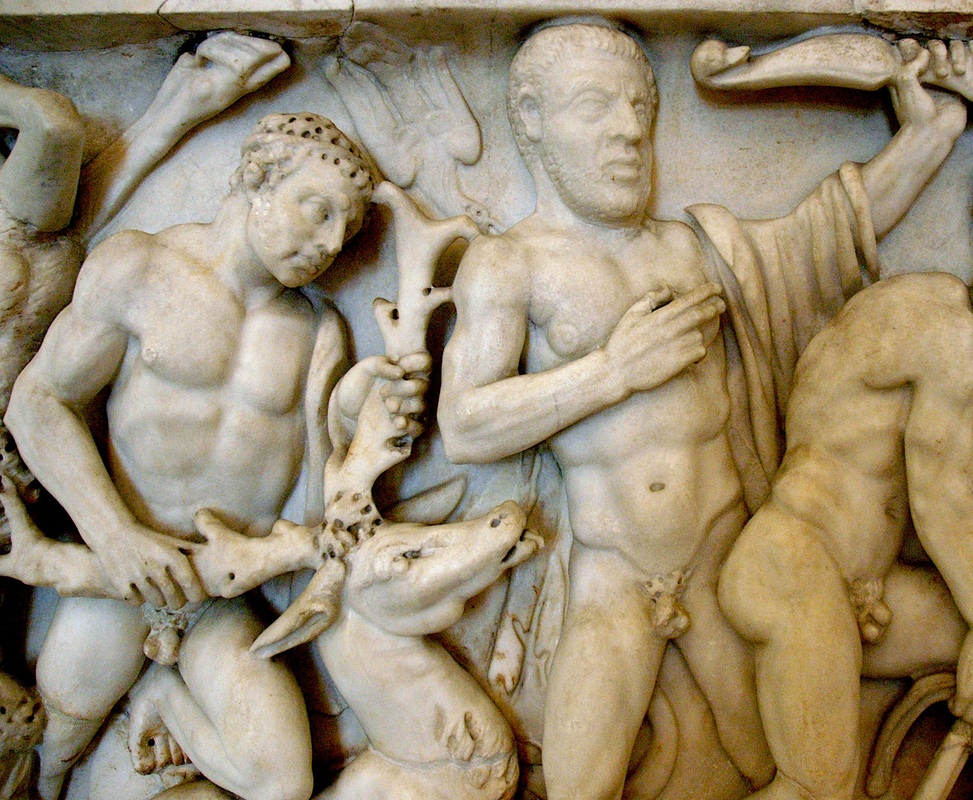

You’ll notice immediately how similar the compositions are. Sure, there are minor differences: the head and torso of the Hydra on today’s piece (second episode from the left) is considerably less monstrous. Eurystheus looks even more ludicrous as he takes refuge in a sunken pithos (a large partially-submerged storage jar) from the Erymanthian Boar slung over Hercules’ shoulder. This sarcophagus gives us two Stymphalian Birds, not one, and neither appears to nibble on Hercules’ bow (instead, one appears to be dive-bombing our hero’s shoulder). And Hippolyta, the Amazon Queen, looks not dead but worrisomely elastic and gumby-like as she spins her head around to look up at her conqueror as he strips her of her girdle. But taken as a whole, these compositions are almost identical.

Was the carver of the second sarcophagus (today’s piece) simply copying the composition of the first directly? It seems unlikely. Some 70 to 80 years separate these two pieces. And the first would almost surely have been in a private family tomb — i.e., not displayed in some public place where other artists might have seen (and copied) it. It turns out that these two more-or-less identical pieces are hardly unique in their copy-cat-dom. Numerous sarcophagi feature the adventures of Orestes, for example, laid out in exactly (or almost exactly) the same way every time. The same holds for sarcophagi staging the murderous story of Medea, the Hunt of the Calydonian Boar, and numerous other myths. They are our best evidence for what was clearly a widespread practice among Roman sculptors: the reliance on so-called pattern books, or copy books: picture books featuring drawings of popular compositions, which carvers could refer to for inspiration as they translated them into stone. Why bother developing one’s own novel composition — and risk months of wasted labor and material if it failed — when one could simply adopt a well-known composition guaranteed to work? Something else you’ve doubtless noticed: the head of the middle Hercules on today's piece — the one shooting the Stymphalian Birds — looks substantially different from the others. That’s because it’s a portrait: a portrait of the deceased man interred within the sarcophagus itself. It may strike us as odd, to see the portrait head of a rather grumpy looking middle-aged Roman man plopped atop the idealized body of Hercules. But it was common Roman practice on sarcophagi between roughly 220 and 250 AD. The Greek mythological imagery on sarcophagi was intended, as a rule, to be applied to the dead Romans buried inside them. Equipping these mythological characters with portrait features of the deceased was a way to make the metaphorical connection between them emphatic: it demanded that the viewer read the mortal through the mythic, and the mythic through the mortal. Which brings us back to the epic saga of facial hair. Hercules on these sarcophagi begins his labors clean-shaven, and develops a beard along the way. We noted last time that it was a strategy for rendering, within the static and immobile terms of stone, the passage of time: a reminder that Hercules’ labors stretched over years. But now, goaded by the portrait to read this dead Roman in terms of the Greek hero, we realize that this device serves an additional purpose. It invites the viewer to imagine the entire adult life of the deceased man — from beardless youth to bearded age — as a single lifelong string of glorious labors and deeds, just like Hercules’. Bombastic? Absolutely. But effective.

Comments warmly invited.

(Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.) This gorgeously carved mythological sarcophagus presents a composition so crowded that you might think it undecipherable. But once you know a few tricks of Roman visual logic, the unruly mass of bodies settles down into order. This sarcophagus stages the Twelve Labors of Hercules. Its method is to line the episodes up in a single row, with no borders separating them, and to repeat the figure of the hero himself twelve times, once for every labor. At this point you may be thinking “Twelve labors?! I only see ten.” Right you are: what we have here is simply the front slab of the sarcophagus. The two missing labors would have appeared on the coffin’s short ends (now missing). So which labors do we have on the front? From left to right, Hercules....

Many of the visual details are whimsical, even quirky. But it’s the changing state of Hercules’ facial hair that is the most interesting. Our hero stays clean-shaven for his first four labors. But then, beginning with the Stymphalian Birds, he suddenly sprouts a beard, and sports it during his remaining exploits. What to make of this? It’s tempting to joke that his labors simply left him too busy to shave. But that doesn’t quite capture the purpose of this artistic device. The progression from baby-faced to bearded hero serves, above all, as a concise way to indicate time’s long passage. The labors took twelve years to complete, occupying the better part of Hercules’ adult life. The development of his facial hair thus indicates the direction of the narrative and tracks the progression of time, rendering it visible within the static and immobile terms of carved stone. We look at another Hercules sarcophagus in our next post: Why does Hercules look like Uncle Rufus?

Comments warmly invited.

(Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.) An earlier post ("Shouldering Responsibility for Recutting") was devoted to a child's sarcophagus with several unusual features. One of them had to do with the child's clothing: she (turned into a portrait of a he) was portrayed wearing sensual off-the-shoulder drapery. Such suggestive garb would be unexpected even for a grown woman: unless she was adopting the guise of Venus, no respectable Roman woman would show herself (un)clad in this way. It would seem an even odder choice for a child. Yet the small dimensions of the coffin left no doubt that it was intended for a child, or at least a juvenile. I filed it away mentally as yet another unique specimen, one of the hundreds of quirky pieces that make the study of Roman sarcophagi endlessly alluring. But it turns out that, while quirky, this feature isn't unique. A colleague has brought another specimen to my attention — from, in fact, the same museum. (The Vatican's collections stretch for halls and halls....) This one, shown above, features a festive procession (in ancient Greek, a thiasos) of various marine creatures: sea nymphs, sea centaurs, dolphins, and, at the far ends, pendant vignettes showing Europa's watery abduction at the hands (horns?) of Zeus in bull's form. The two sea centaurs in the center bear a clipeus medallion framing a portrait of the deceased. As so often, the portrait itself is unfinished: the facial features are still blank, waiting for the final customization once a customer had been found. But the rest of the bust has already been executed — and it clearly shows the same revealing off-the-shoulder drapery as our other piece. Finally, this coffin too was intended for a juvenile: its dimensions are too small for an adult. What's the deal with the sexy kids? I don't have an answer yet — only the beginnings of a pattern. I can't help but wonder, though, whether these pieces were intended for girls who died close to the age of marriage (as young as 12 years for aristocratic girls), their revealing garb meant to underscore the poignancy of a life cut down before its beauty could find adult consummation.

Comments warmly invited.

(Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.) The small dimensions of this piece reveal that it was intended for a child. Given the high rates of infant and juvenile mortality in the ancient world (as in most pre-industrial societies), it is perhaps no surprise that many Roman sarcophagi were carved for children. The sheer number of such pieces is, nonetheless, poignant. The portrait was clearly reworked in antiquity itself: originally intended to depict a young woman or girl, it was recarved to portray a (rather strikingly ugly) boy. That's not especially unusual: as we've already seen, recutting of portraits for reuse by other inhabitants was a common practice, and could even involve sex-changes along the way, as here. What is unusual here is our diminutive subject's off-the-shoulder drapery. It's so suggestive that one might wonder whether the original figure was meant to show Venus, or rather a woman in the guise of Venus. But while the occasional Roman matron was indeed portrayed in the costume and pose of the goddess — a form of mythological portraiture — such mythological portraiture, as far as I know, is never found inside the frame of a tondo/medallion (the Romans called it a clipeus, their word for 'shield', because of its round shape). When Romans equip themselves with the attributes of gods or heroes on sarcophagi, it's always as a full-body figure within a narrative frieze, not a bust isolated within a clipeus. But without the excuse of mythological trappings, what respectable Roman female would choose commemoration in such sexy garb? That it features on a child's sarcophagus makes things even more puzzling. On a different note... the motif of two fowl pecking the ground under the clipeus was clearly a stock vignette, as this piece shows. Comments warmly invited. (Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.) Why does this sarcophagus have rounded ends? Why the lions' heads, and why are they chomping on rings? Because — and you'll probably think this kooky — this sarcophagus is carved in the shape of a wooden wine vat. The rounded ends are characteristic of the large tubs in which Romans pressed grapes to make wine. More importantly, so are the lions: we know from ancient depictions of actual Roman wine troughs that they often carried fancy felines' heads, carved in relief near the ends of the vat. These served as elaborate (and humorous) decoration for the spigots (!) installed in their mouths: wine flowed from the ferocious maws of lions — if you dared to put your hand directly between their jaws to open the tap. They met other functional needs as well. The metal rings used as handles for hoisting and dragging the vat had to be embedded in something; and ideally that something would project outward from the rest of the tub, to make carrying easier. These leonine bosses thus served as anchors for carrying handles ("Think you can handle a lion? Now you can!") as well as fanciful frames for spigots. Here the form of one of those elaborate wine tubs has been translated into stone, to hold very different contents. This was a popular format for sarcophagi: many elite Romans commissioned this style of coffin, particularly during the third century. Just imagine a wealthy businessman or an important Senator choosing a stone-imitation wine vat as his vessel for eternity. This would be unthinkable for us. But it was entirely unproblematic for Romans, who so often — unlike us — preferred to meet death with humor. As a side note.... you'll observe that the marble from which this sarcophagus was carved has several bands of darker color that run through the stone. There's a wide, very dark band near the bottom; and a set of lighter, blue-gray bands that run across the top. That's a characteristic feature of marble quarried on the island of Proconnesus (now Marmara), not too far from Istanbul, in modern-day Turkey. It was a popular choice of stone for Roman sarcophagi in the third century. You might think it an odd choice, given how far Proconnesus is from Rome. But transport by sea was far easier and faster than transport over land in antiquity. And the quarries on the island were close to the water — unlike the quarries of Italy. As a result, shipping marble all the way from Turkey to Rome was actually cheaper than using marble from Italy itself. Comments warmly invited. (Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.) Why does this young man appear to be sprouting phantasmic locks of hair from above his left ear? It seems that he's shadowed by the ghostly ponytail of the coffin's previous owner. The portrait has clearly been recut, and the original must have showed a boy devoted to the goddess Isis: her young male followers proclaimed their devotion by shaving their heads, razoring off everything except a single long tuft of hair above the ear. (The hairstyle was modelled on that of the mythic child Harpocrates, son of Isis.) Sheer need must have driven the later family to choose this piece — with its prior owner's prominently protruding hairstyle — for reappropration and recutting. Why not choose one with a portrait of a non-devotee, whose hair would be much less troublesome to erase? Or else simply make better use of abrasives to take down the background plane around the head, fully scrubbing off any lingering halo? Clearly money — or time — was limited, and the family made do with the used piece they had at hand: a striking reminder of the exigencies of death, the high rates of infant mortality in the ancient world, and above all, the frequent recarving and reuse of sarcophagi in antiquity by Romans themselves. ADDENDUM I return to this piece in a later post: The Phantom Ponytail returns. Comments warmly invited. (Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.) Who is that boy who stands languidly with arms atop his head, doing his best impression of a male pin-up on both ends of this sarcophagus? And why is there a cupid at his feet, pointing to what looks like a theater mask on the ground? If he weren't doubled up, you might think he was Dionysus, or even Apollo, given the youthful features and the erotic posturing. But since he's duplicated, he probably doesn't represent a deity: Roman carvers often duplicated generic figures, and sometimes even mythological mortals; but they usually refrained from doubling up a god. So who is he? The answer: Narcissus. He's very uncommon: out of roughly 15,000 surviving Roman sarcophagi, only 5 (!) show Narcissus. But this is he. The cupid — that wee godling of desire — who stands at his feet is pointing not to a theater mask, but to Narcissus's own reflection. Which Narcissus, of course, is admiring: the erotic nature of his pose reflects his response to his own image. The composition seems bizarre to us: doesn't the Narcissus of Ovid's story (Metamorphoses 3:402-436) bend over the pool, or rather, lie beside it, rather than stand erect over it? Indeed he does. But the formal parameters of this particular format of sarcophagus, which left a tall but narrow field for mythological depiction at each end, imposed its own restrictions. If Narcissus and his reflection — plus a symbolically helpful (though in Ovid's original narrative, entirely absent) cupid — were all to be shown within this constricted space, our self-asorbed hero would have to stand. Comments warmly invited. (Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.)

The portraits of the deceased husband and wife who inhabited this Roman sarcophagus were never finished: their faces are blank. That's not very unusual, actually. What is unusual are the mushroom-like lumps poking out just underneath the busts. What are those things?

They must be the couple's preliminary and uncarved hands. But note that while these haven't yet been chiselled, they have been drilled: the perfectly round drill holes are unmistakable. This provides insight into the order of operations of a typical Roman workshop. The drill was used first, for initial indexing (in this case, to index the separation of the fingers). Only after this did the sculptor plan to turn to the chisel for further differentiation of the digits. This particular sarcophagus, however, was pressed into service before he had time to complete that next step — ensuring that our dead couple would remain not only faceless, but forever fingerless. EDIT: I have since been informed that what I took to be uncarved hands are more likely acanthus leaves, for which a handful of other pieces provide precedent. This must surely be right. Also notable is the vignette directly underneath the central tondo. It shows a marvelous bucolic scene: a seated shepherd helps a ewe give birth (!). James Herriot would be proud. But in a funerary context this motif would have carried extra resonance: the imminent birth of a lamb stands in counterpoise to the deceased couple directly above, insisting on life's continuity in the face of death.

Comments warmly invited.

(Both the Facebook system below, and the traditional comment form, work dandily.) |

Roman

|